MEXICO CITY — Andrea Paola Hernández has one sister in Ecuador and another in London. She has cousins in Colombia, Chile, Argentina and the United States.

All fled poverty and political repression in Venezuela. Hernández, a human rights activist and outspoken critic of the country’s authoritarian leader, Nicolás Maduro, eventually left, too.

Since 2022 she has lived in Mexico City, working odd jobs for under-the-table pay because she lacks legal status. She cries most days, and dreams of reuniting with her far-flung relatives and friends. “We just want our lives back,” she said.

One of Maduro’s darkest legacies was the exodus of 8 million Venezuelans during his 13-year rule, one of the largest mass migrations in modern history. The flight of a third of the country’s population ripped apart families and has shaped the cultural and political landscape in the dozens of nations where Venezuelans have settled.

The surprise U.S. operation to capture Maduro this month has prompted mixed feelings among the diaspora. Relief, but also apprehension.

From Europe to Latin America to the U.S., those who left are asking whether they finally can go home. And if they do, what would they return to?

‘An ounce of justice’

Hernández was distressed by the U.S. attack, which killed dozens of people and is widely seen as illegal under international law. Still, she celebrated Maduro’s arrest as “an ounce of justice after decades of injustice.”

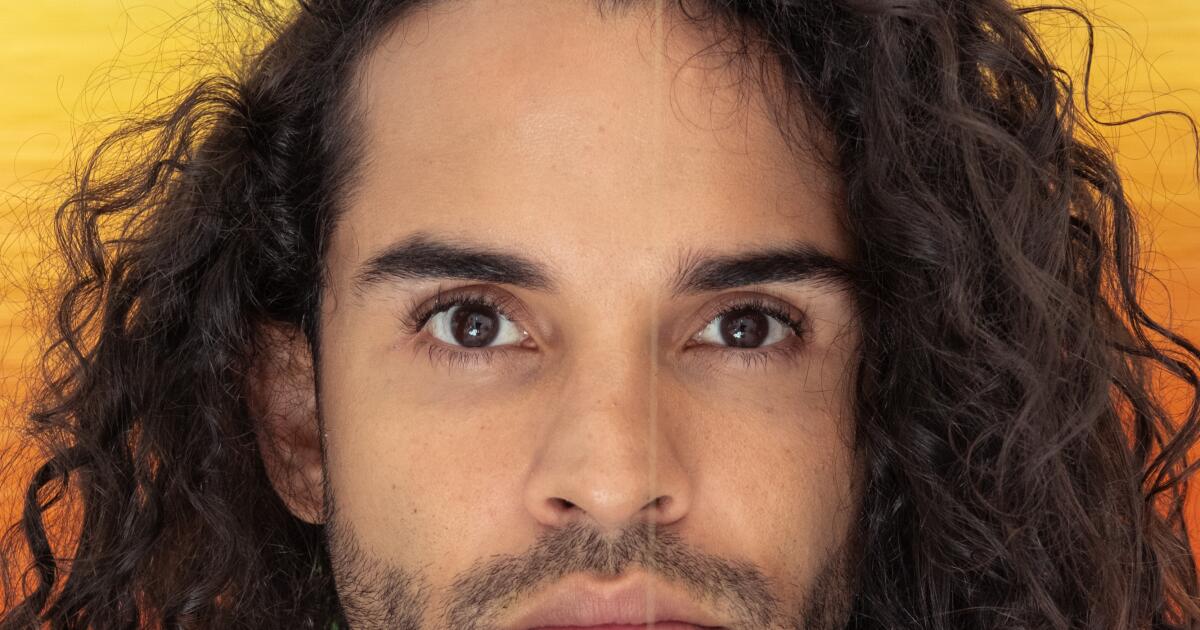

Andrea Paola Hernández, 30, an Afro-Indigenous, queer, feminist activist and writer from Maracaibo, Venezuela, stands for a portrait on the roof of her building on Friday in Mexico City. Hernández left Caracas in 2022.

(Alejandra Rajal / For The Times)

She is wary of what is to come.

President Trump has repeatedly touted Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, saying little about restoring democracy to the country. He says the U.S. will work with Maduro’s vice president, Delcy Rodríguez, who has been sworn in as Venezuela’s interim leader.

Hernández doesn’t trust Rodríguez, whom she believes is as responsible as anyone else for Venezuela’s misery: the eight-hour lines for food and medicine, the violent repression of street protests and the 2024 election that Maduro is widely believed to have rigged to stay in power.

Hernández blames the regime for personal pain, too. For the death of an aunt during the pandemic because there was no electricity to power ventilators; for the widespread hunger that caused her mother to tell her children: “We can have dinner or breakfast, but not both.”

Hernández, who believes she was being surveilled by Maduro’s government, says she will return to Venezuela only after elections have been held. “I’m not going back until I know that I’m not going to be killed or put in jail.”

‘Our identity was shattered’

Many in the diaspora are trying to reconcile conflicting emotions.

Damián Suárez, 37, an artist who left Venezuela for Chile in 2011 and who now lives in Mexico, said he was surprised to find himself defending the actions of Trump, a leader whose politics he otherwise disdains.

“We were fragmented and demoralized, and then someone came along and imprisoned the person responsible for all of that,” Suárez said. “When you’re drowning, you’re going to thank the person rescuing you, no matter who it is.”

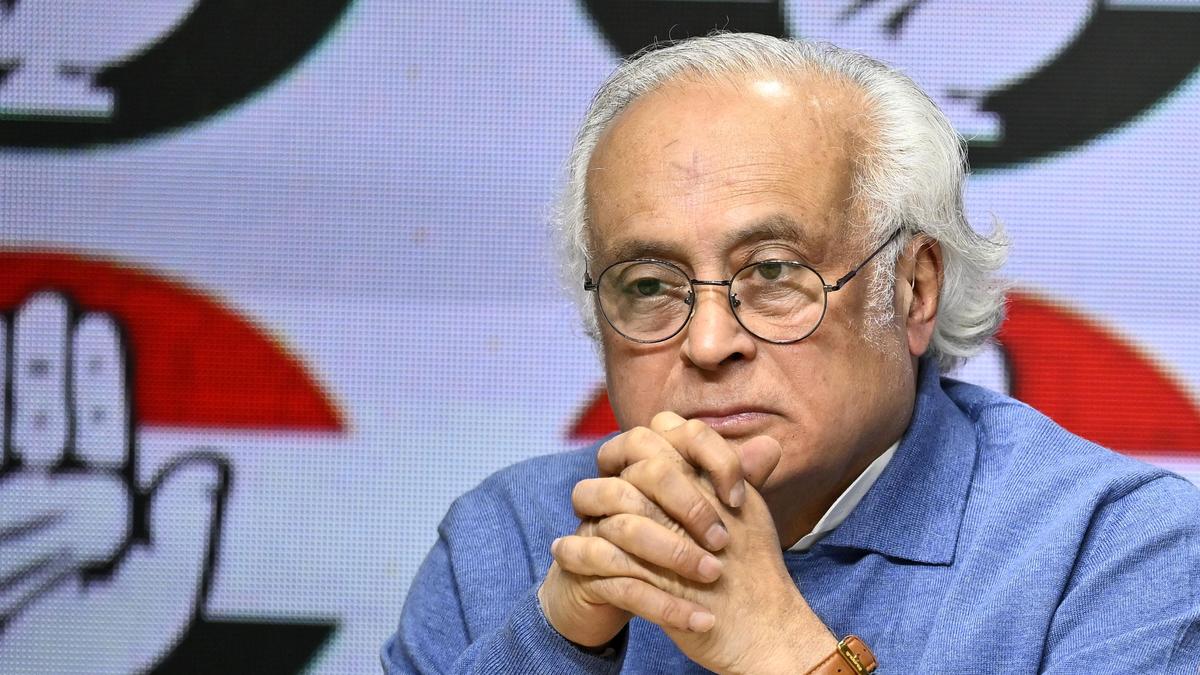

Damián Suárez at his studio in the Condesa neighborhood on Friday in Mexico City. He arrived from Venezuela in 2011 and works as an artist and curator.

(Alejandra Rajal / For The Times)

Many countries have denounced the attack on Caracas and Trump’s vow to “run” the country in the short term as an unacceptable violation of Venezuela’s sovereignty.

For Suárez, those arguments ring hollow. For years, he said, the international community did little to mitigate the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela.

“A cry for help from millions of people went unanswered,” Suárez said. “The only thing worse than intervention is indifference.”

One of the first embroidery art works made by Damián Suárez as a child on display in his studio, in la Condesa in Mexico City. To this day, he uses string as his primary material, a form of resistance and defiance rooted in the hand-labor traditions of the community he comes from.

(Alejandra Rajal / For The Times)

Suárez, who is organizing an art show about Venezuela, blames Maduro for what he sees as a “spiritual void” among migrants who lost not just their physical home but also the people who gave meaning to their lives.

“Our identity was shattered,” he said, comparing migrants with “plants ripped from their soil.”

And though Maduro now sits in a jail in Brooklyn facing drug trafficking charges, Suárez said he will not go back to Venezuela.

He has a Mexican passport now and helped his family migrate to Mexico City. After years of feeling stateless, he’s finally planted roots.

Building lives in new countries

Tomás Paez, a Venezuelan sociologist living in Spain who studies the diaspora, says that surveys over the years show that only about 20% of immigrants say they would return permanently to Venezuela. Many have built lives in their new countries, he said.

Paez, who left Venezuela several years ago as inflation spiraled and crime spiked, has grandchildren in Spain and said he would be loath to leave them.

“There isn’t a family in Venezuela that doesn’t have a son, a brother, an uncle, or a nephew living elsewhere,” he said, adding that 50% of households in Venezuela depend on remittances from abroad. “Migration has broadened Venezuela’s borders. We’re talking about a whole new geography.”

Migrants left Venezuela under diverse circumstances. Earlier waves left on flights with immigration documents. More recent departees often take clandestine overland routes into Colombia or Brazil or risked the dangerous journey across the Darien Gap into Central America on their way north.

The restriction of immigration law across Latin America has made it harder and harder for migrants to find refuge. One fourth of Venezuelan migrants globally lack legal immigration status, Paez said. And a majority don’t have Venezuelan passports, which are difficult to acquire or renew from abroad.

‘So tired of politics’

Throughout the Western Hemisphere, enclaves of Venezuelans have sprouted up, such as one in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, a Mexican town near the border with Guatemala.

Richard Osorio ended up there with his husband after a stint living in Texas. Osorio’s husband was deported from the U.S. in August as part of Trump’s crackdown on Venezuelan migrants. Osorio joined him in Mexico after a lawyer told him that U.S. immigration agents might target him, too, because he has tattoos, even though they are of birds and flowers.

The pair are undocumented in Mexico and work for cash at one of the Venezuelan restaurants that have sprung up in recent months.

On the day of the U.S. operation that resulted in Maduro’s arrest, hundreds of Venezuelans cheered the news in a local square. Osorio was working a 14-hour shift and missed the party. It was fine. He didn’t have the energy to celebrate.

“I’m so tired of politics, of these ups and downs that we’ve experienced for years,” Osorio said. “At every turn, there’s been suffering.”

Richard Osorio poses for a portrait in Juarez, Mexico, in July.

(Alejandro Cegarra / For The Times)

He had a hard time conjuring warm feelings for Trump given the U.S. president’s war on immigrants, including the deportation of more than 200 Venezuelans that he claimed were gang members to an infamous prison in El Salvador.

Maduro and Trump, he said, are more alike than many people admit. Neither cares for human rights or democracy. “We felt the same way in the U.S. as we did in Venezuela,” Osorio said.

He said he wouldn’t return to Venezuela until there were decent jobs and protections for the LGBTQ+ community. Life in southern Mexico was dangerous, he said, and he wasn’t earning enough to send money to relatives back home.

But returning to Venezuela didn’t feel like an option yet.

Daring to dream

Hernández, the writer and activist, said many in the diaspora are too traumatized to imagine a future in Venezuela. “We’ve all been deprived of so much,” she said.

But when she dares to dream, she pictures a Venezuela with free elections, functioning schools, hospitals and a vibrant cultural scene. She sees members of the diaspora returning, and improving the country with the skills they’ve learned abroad.

“We all want to go back and build,” she said. The question now is when.