- Scientists have identified a naturally recurring weather pattern called Tropics-Wide Intraseasonal Oscillation (TWISO), that occurs in a 30 or 60-day cycle and affects weather over the entire tropics.

- Since seasonal changes and slower phenomena like the El Niño Southern Oscillation, spanning a few years, dominate the tropical climate, interseasonal patterns had not been investigated so far.

- Independent researchers say that TWISO and its relationship with other slow weather variations needs to be studied further.

Scientists analysing two decades of satellite observations and global weather reanalysis data have uncovered a previously overlooked rhythm in the tropical climate system. Jiawei Bao, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), Austria, and his collaborators have identified a naturally recurring weather pattern that they call the Tropics-Wide Intraseasonal Oscillation (TWISO) which influences the tropical belt. Their study was recently published in the journal PNAS and explains how TWISO affects the weather over the Indian peninsula.

A single TWISO cycle lasts about 30 to 60 days and affects the weather in the tropics, including India and the surrounding Indian ocean. It was previously undetected because scientists do not expect a pattern that spans the entire tropical latitudes, affecting rainfall, clouds, and winds over several weeks. This finding could bridge the gap between the understanding of daily and seasonal weather patterns.

Why this phenomenon remained hidden

The accidental discovery of TWISO stems from an observation in 2024, when the group was studying something different. They investigated the relationship between the degree of cloud clustering over tropical latitudes and extreme rainfall events in these regions. This relationship would have enabled them to accurately predict extreme rainfall. While studying the day-to-day variations of the two parameters, they observed a striking pattern: they repeated every 30 to 60 days. They used the same data to determine that other parameters, such as sea surface temperature, atmospheric temperature, and the amount of heat exchanged by the Earth across the atmosphere, also show similar variation.

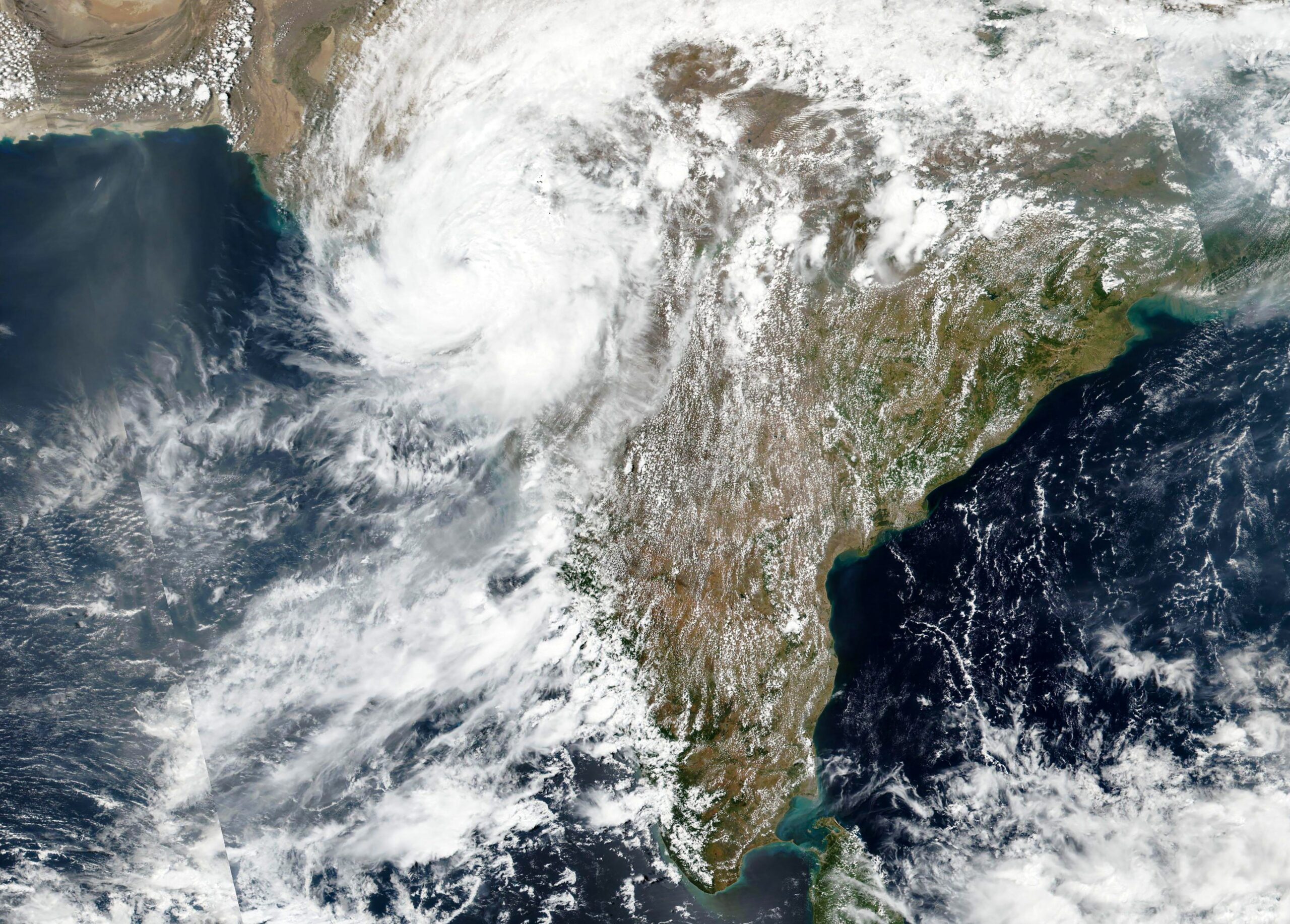

Weather predictions typically span a few days, whereas seasons vary over many months and affect the weather gradually. During these periods, atmospheric circulations regulate wind, temperature, and climate across large regions of the Earth. They distribute matter, energy, and momentum across regions — in this case, the tropical zone from 30°N to 30°S, encompassing Africa, Asia, Australia, and the central and southern Americas. In extreme cases, they can even lead to tropical storms like cyclones that wreak havoc, especially in the Indian subcontinent.

Bao explained that climate researchers do not investigate phenomena over interseasonal periods because seasonal changes and even slower phenomena like the El Niño Southern Oscillation, spanning a few years, dominate the tropical climate. That is why the faster variation across the entire tropical latitudes, somewhere between days and seasons, remained hidden until now. While studying the relationship between how clouds cluster together over these regions and subsequent rainfall, their repetitive behaviour over 30 to 60 days stood out. “That really caught my interest and attention,” said Bao.

Further exploration revealed that these variations reflected atmospheric and sea-surface temperatures, as well as the net amount of heat the Earth exchanges with the atmosphere. As these quantities vary in cycles, the tropical weather may change over two weeks or over a month. “The intraseasonal oscillations affect the weather over the entire tropics,” Bao said.

“The large-scale tropical overturning circulation is not static but pulses system-wide like a heartbeat,” said Vishal Dixit, a climate researcher at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, who was not involved in the study.

“It may link to active and break spells in the Indian monsoon,” added Chirag Dhara, a climate researcher at Krea University who was also not a part of the study. Dixit noted that during the active phase, monsoon rainfall may increase, whereas during the suppressed phase, the air is cooler and drier, resulting in reduced rainfall.

TWISO and the weather

Bao and his collaborators identified that convection plays an important role in regulating the tropical atmosphere. “If you have cold air above the warm air, it’s not stable, so that the air will rise,” explained Bao. That movement causes the air to condense vapour, which warms it, driving it upward even further. Scientists call this movement convection.

In the tropical atmosphere, convection happens over the western part of the Pacific Ocean, where the sea-surface temperature is the highest. The air falls back onto the ocean in the eastern part of the Pacific Ocean, leading to a circulation pattern. At the same time, another circulation takes place perpendicularly, in the north-south direction, across the latitudes, between the equator and the 30° latitudes. The researchers found that these two circulations are dependent on each other.

This kind of circulation is not new, however, another oscillation across the tropical zone, spreading east-west, known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), moves warm air eastward in the atmosphere and westward over the oceans. The entire oscillation moves eastwards across the globe. The effect of this oscillation on the newly identified tropics-wide intraseasonal oscillation (TWISO) remains uncertain. While it can amplify TWISO, it is not essential for TWISO to occur in the first place. “This paper presents an interesting viewpoint, but the independence of MJO from TWISO needs to be further explored and supported with more data analysis,” said Dixit.

Moreover, it is unclear why these oscillations couple, although the team has hypotheses. Bao and his colleagues plan to test these mathematically and compare the predictions with the discovery. “It is unclear whether even state-of-the-art climate models can capture TWISO oscillations reliably,” said Dhara.

“Identifying the phenomenon (TWISO) is just the first step,” admitted Bao, “as it opens up lots of new follow-up questions.” Dixit suggested that “the key aspect would be [to] segregate and filter MJO signals from TWISO signals.”

Bao is keen to understand what drives the newly discovered oscillation, how it interacts with the Madden-Julian Oscillation, and how exactly it can influence weather and extreme events in the tropics.

Read more: The global links behind India’s cold weather

Banner image: A satellite image shows cyclone Tauktae approaching India’s western coast. (NASA Worldview, Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) via AP)