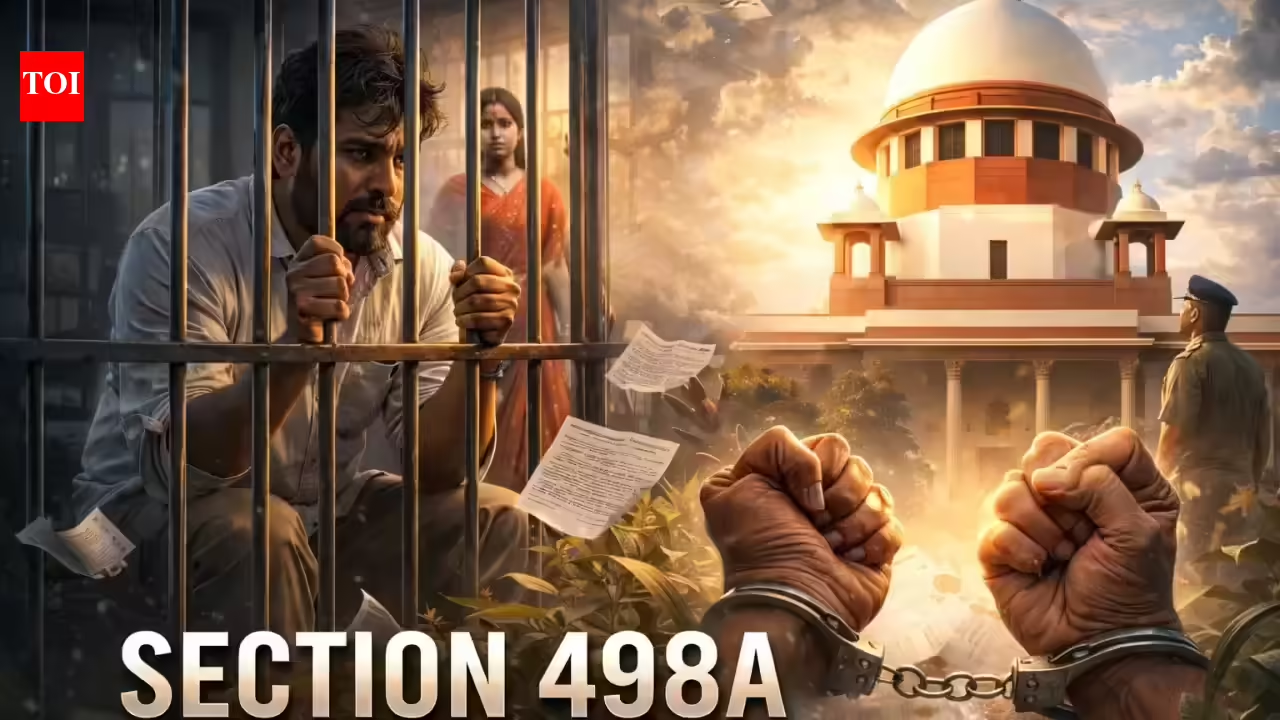

In a significant judgement delivered on 22.07.2025, the Supreme Court pointed out that though laws protecting women against cruelty and dowry harassment cannot be eliminated, misuse of the same has to be stopped in order to stop ruining lives and families.Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code was introduced to provide a strong remedy against the institutionalized social vice of dowry harassment and inhumanity against married women. Throughout the decades, the provision has rescued a great number of women who are abused in the matrimonial home. However, alongside its indisputable significance, courts have frequently been confronted with cases where the provision has been applied in a broad and blanket fashion, dragging whole families into a criminal prosecution before the dust of a marriage break had settled.It is this ongoing conflict between protection and excess which provided the background to the action of the Supreme Court in Shivangi Bansal v. Sahib Bansal. In this case, the Court not only settled a bitter matrimonial feud, but also reinstated the Allahabad High Court structure of Family Welfare Committees (FWCs) as a procedural protection measure to prevent abuse of Section 498A.The couple, Shivangi Bansal and Sahib Bansal, got married in December 2015 as per Hindu tradition. In December 2016 a daughter was born. After years of marriage, severe matrimonial problems emerged and the parties parted ways in October 2018. What followed was an extraordinary flood of law suits. The wife filed several criminal charges against the husband and his kin, which included a broad-based FIR that referenced Sections 498A, 307, 376, 377, 313, and 120B of the IPC, and the Dowry Prohibition Act. It was followed by domestic violence proceedings, maintenance cases, criminal breach of trust complaints, and a number of revisions and special leave petitions.The husband and his family, in turn, also initiated proceedings against the wife and her relatives. The conflict escalated into parallel litigation in courts in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh and even to the Supreme Court involving even third parties and a full meltdown in family and social relationships.The cumulative effect of these proceedings was devastating. The husband had served 109 days in jail with his father serving 103 days in jail even though the charges were later dropped. The Court observed that damage to the family in terms of social, psychological and professional issues was irreparable.The bench led by Chief Justice B.R.Gavai and Justice Augustine George Masih found it prudent to protect against abuse of Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, upheld the Family Welfare Committee (FWCs) constitution as provided by the Allahabad High Court and in a rare decision ordered a wife to issue an unconditional apology publicly following the conclusion that false and sweeping criminal charges had caused the husband and his family to spend in prison.The Court also used its extraordinary powers under Article 142 of the Constitution to break up the marriage, terminate all the pending civil and criminal cases between the parties and bring a total and final stop in years of fruitless litigation.In a sweeping order, the Court:

- Quashed all civil and criminal proceedings between the parties and their families across the country;

- Dissolved the marriage by mutual consent;

- Settled custody, visitation, and maintenance issues;

- Directed a public unconditional apology by the wife to the husband and his family for the false cases filed;

- Granted police protection to the husband’s family; and

- Restrained both parties from initiating any future litigation arising out of the matrimonial dispute.

The Supreme Court further took care to explain that abuse of Section 498A does not in any way erode its constitutionality or social utility. At the same time, it acknowledged a growing tendency where criminal law is deployed as a pressure tactic in matrimonial disputes, often without regard to proportionality or truth.In this context, the Supreme Court expressly referred to and upheld the Allahabad High Court’s approach, which had sought to provide a structured buffer between the filing of a complaint and the coercive mechanism of arrest.That the concept of Family Welfare Committees traces its roots to Rajesh Sharma v. State of U.P. (2017), where the Supreme Court had initially experimented with committee-based scrutiny before arrests. That approach was later recalibrated in Social Action Forum for Manav Adhikar v. Union of India (2018), where the Court warned that judicial overreach and the development of comparable statutory mechanisms were prohibited.Despite this, the Allahabad High Court, taking note of persistent misuse concerns, framed detailed procedural safeguards, carefully attempting to strike a balance between protection and prevention of abuse.The Allahabad High Court directed the following safeguards, which now stand endorsed by the Supreme Court:Cooling-Off PeriodAfter the lodging of an FIR or complaint involving Section 498A (along with allied offences carrying punishment below 10 years and excluding serious offences like Section 307 IPC), no arrest or coercive action shall be taken for a period of two months.Mandatory Reference to Family Welfare CommitteeDuring this cooling-off period, the matter must be referred to a Family Welfare Committee (FWC) constituted in each district.Composition of FWCsEach district shall have one or more FWCs under the District Legal Services Authority, comprising at least three members, such as:

- Young mediators or advocates with up to five years’ practice;

- Senior law students with strong academic credentials;

- Recognised social workers with clean antecedents;

- Retired judicial officers; or

- Educated spouses of senior judicial or administrative officers.

Role and FunctionThe FWC is required to:

- Summon both parties along with up to four elderly family members each;

- Facilitate dialogue and attempt reconciliation;

- Prepare a reasoned report within two months addressing factual aspects and its opinion.

No Witness RoleMembers of the FWC cannot be cited as witnesses in any subsequent proceedings.Limited Police ActionWhile arrests are barred during the cooling-off period, police may conduct peripheral investigation, such as medical examination and recording statements.Post-Report ActionAfter receiving the FWC report, the Investigating Officer or Magistrate is free to proceed in accordance with law, based on the merits of the case.Training and OversightFWCs are to receive periodic training, and their functioning is to be reviewed by the District & Sessions Judge or Principal Judge, Family Court.The fact that this framework was approved by the Supreme Court is a judicial breakthrough: it does not mean that the Section 498A will be weakened, but instead the humanization of its application will be done.(Vatsal Chandra is a Delhi-based Advocate practicing before the courts of Delhi NCR.)