It was like a horror movie. The invisible polio virus would strike, leaving young children on crutches, in wheelchairs or in a dreaded “” ventilator. Each summer, the fear was so great that . Parents , afraid their child might be the next victim. A U.S. president paralyzed by polio called for Americans to to support the nonprofit , established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his lawyer, Basil O’Connor. Celebrities from Lucille Ball to Elvis were enlisted to promote this “March of Dimes,” and mothers went door to door raising funds to conquer this dreaded disease.

Some of those funds went to 33-year-old scientist Jonas Salk and his team at the University of Pittsburgh, where they worked in a lab between a morgue and a darkroom to develop the world’s first successful polio vaccine.

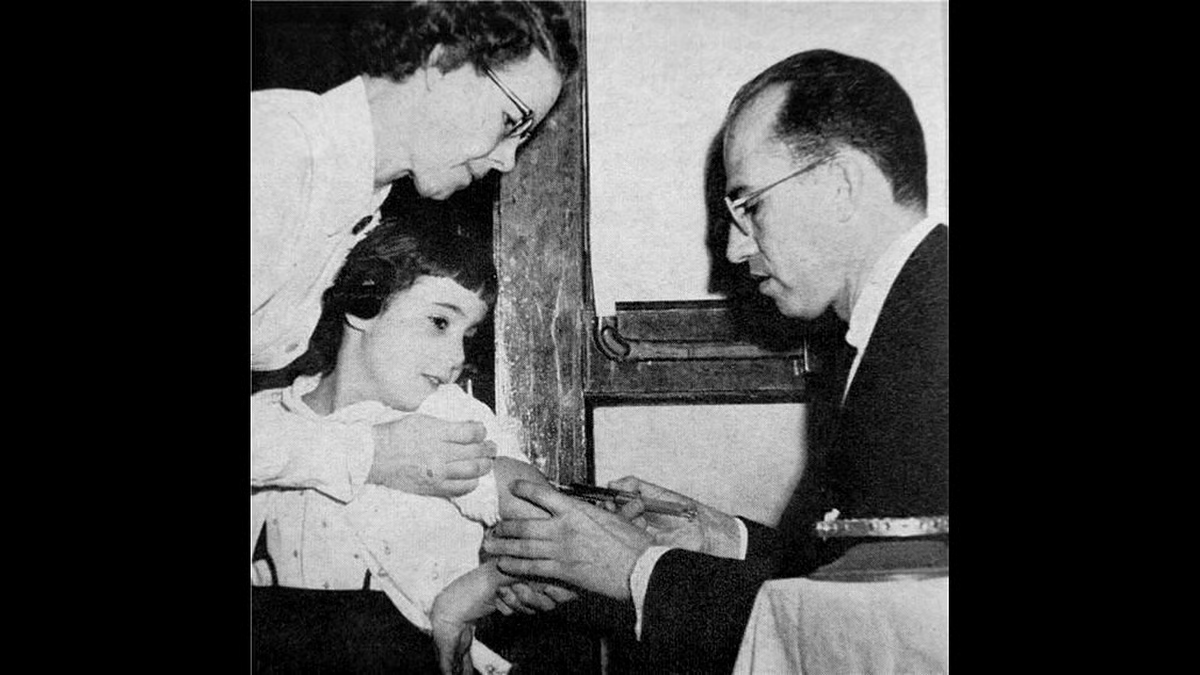

To prove it worked, the experimental vaccine was and then from around the country as part of the largest medical field trial in history. On April 12, 1955, when the Salk polio vaccine was declared “,” church bells rang out, kids were let out of school, and celebrated the victory over polio.

When asked whether he was going to patent the vaccine, Salk told journalist Edward R. Murrow it belonged to the people and would be like “.”

I first learned about this 20 years ago when my students and I filmed the 50th anniversary celebration of the Salk polio vaccine at the University of Pittsburgh. I had just started teaching after working in Los Angeles as a screenwriter and TV producer, and the footage became “,” a documentary that featured those we met that day.

The ‘Pittsburgh polio pioneers’

Among the people we interviewed was , who worked in the lab pipetting the deadly polio virus , and , the lab’s senior scientist who had worked on the Manhattan Project before coming to Pittsburgh. Within a decade, Youngner had worked on the scientific achievement that , the atomic bomb, and one that did great good by sparing millions from the scourge of “[The Great Crippler].”

Three floors above the lab, performed tracheotomies on 2-year-old iron lung patients, opening their windpipes so the ventilator could help them breath. The fierce , an innovator in the field of rehabilitation sciences, ran the polio ward, and she was also the medical director of the , where the Salk vaccine was first tested on humans. Polio victims like and volunteered themselves as guinea pigs for a vaccine they knew would never benefit them.

Many “,” as they called the local children who were given Salk’s still-experimental vaccine, in our documentary recalled getting the shot from Salk himself. Salk also gave it to his own children, including his eldest son, , then 10 years old, who later worked with his father on trying to develop an AIDS vaccine.

While Jonas Salk became the most famous scientist in the world, his relationship with the University of Pittsburgh , and the administration rejected his plans for an institute. As a result, the was built in 1963 on the coastline in La Jolla, California, where it .

Near the end of his life, Salk would say sometimes he would run into people who didn’t know what polio was, and he found that gratifying. But today the world is paying a high price for those who don’t remember what life was like before these events and now . The polio virus may not be visible, but it is still with us.

The final mile to eradication

On Oct. 24, 2025, as the Salk vaccine turned 70, I was invited to screen the trailer for “” at a World Polio Day event on Roosevelt Island in New York City, in a building next to the ruins of the Smallpox Hospital – a legacy of the only human disease ever eradicated.

Those present included the executive director of UNICEF, the polio director from the Gates Foundation, the U.N. representative for Rotary International and government officials from around the world who spoke about the global coalition dedicated to eradicating this disease. Since the 1980s, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative has put tremendous resources into taking polio from being endemic in 125 countries to now just in two: . This group, whom I like to call “The Avengers of Public Health,” continue to work relentlessly to make the world polio-free.

My greatest fear is that when polio is finally defeated, the world won’t recognize what an extraordinary achievement it is. In our film, , Jonas Salk’s youngest son, recalls his father wondering whether the model that developed the polio vaccine could be used to conquer poverty and other social problems.

Many of the polio survivors we spoke to at the 50th anniversary are no longer with us. To ensure that future generations know this story, perhaps now is the time to launch a “March of Dimes” marketing technique to engage young people from around the world to help finish the job that began in the Salk lab in Pittsburgh.

One polio survivor who is still alive is “” director Francis Ford Coppola, who has spoken about . Imagine him being interviewed by his granddaughter , a TikTok influencer, and his daughter , the film director and actress. They could make a video that features cameos from actor and comedian Bill Murray, who and whose sister had polio; and U.S. Sen. Mitch McConnell, who is a ; and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, whose . For such a cruel disease, polio has a strange way of bringing us together.

I pray that when we finally wipe polio off the planet, a feat the Global Polio Eradication Initiative , the whole world will celebrate and realize the power of pulling together to defeat a common enemy.

Read more of our stories about , or sign up for our Philadelphia .

, Senior Lecturer, Film and Media Studies,

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .