Astronomers from India have discovered the second farthest spiral galaxy in the depths of the universe, using the powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and have named it ‘Alaknanda’.

The galaxy was an unexpected sight during a broader study of galaxy shapes in the early universe. The findings were published in Astronomy & Astrophysics in November.

The study’s lead author Rashi Jain, a PhD student at the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics in Pune, was analysing public JWST data from the UNCOVER survey, which contains about 70,000 objects, to understand the morphologies of galaxies in the early universe. That’s when she stumbled on the galaxy with two perfectly symmetrical spiral arms.

The first question that popped into her mind was: “Should this exist so early in the universe?”

‘Meticulous analysis’

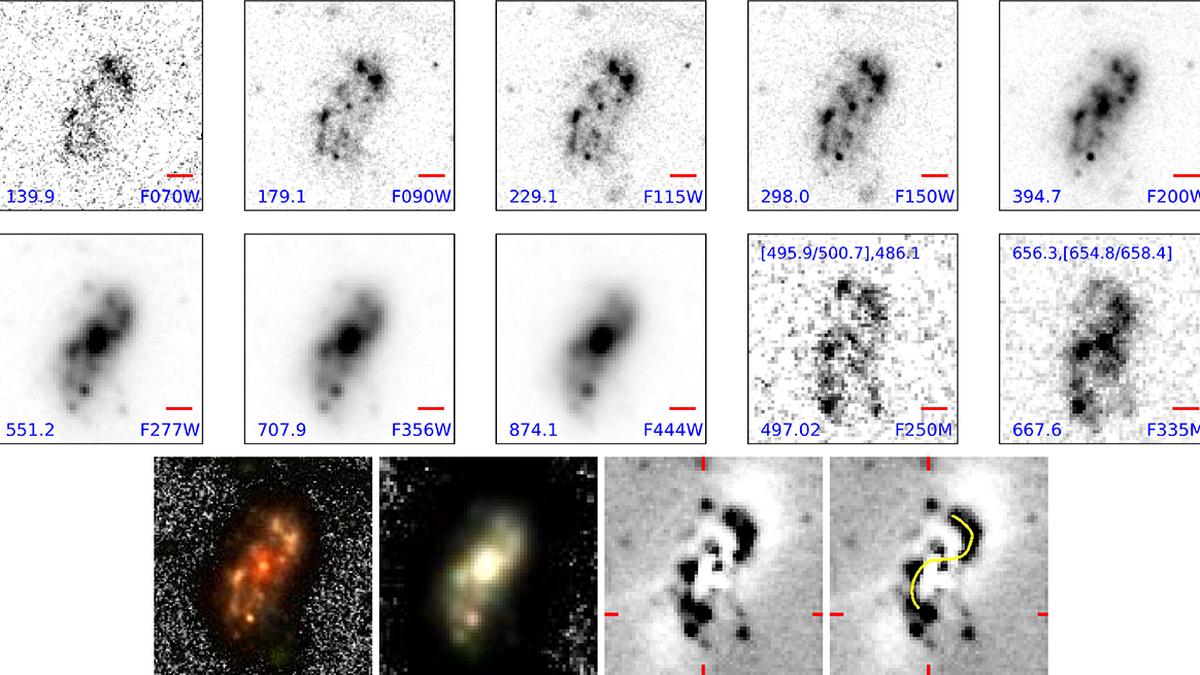

Ms. Jain and her doctoral advisor Yogesh Wadadekar undertook a detailed study to determine the galaxy’s nature. They found it had a prominent disk with two clear spiral arms and a small central bulge. When they removed the smooth light from the disk and the bulge, the spiral arms remained visible, confirming they were real and not an artifact in the light data.

They also found that new stars formed along the spiral arms at about equivalent to 60 stars of our sun’s mass every year. This confirmed Alaknanda was a fully developed spiral galaxy, and only 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

Ms. Jain named the galaxy ‘Alaknanda’ for the river in Uttarakhand. She was looking for a female name to be consistent with how galaxies are often referred to in Indian languages.

“I remembered seeing Alaknanda and Mandakini, both tributaries of the Ganga, flowing together during my visit to Uttarakhand. Since our own Milky Way is called Mandakini in Hindi and is also a spiral galaxy, I named this one Alaknanda,” she said.

“The discovery is serendipitous and the result reflects the power of JWST-quality data and meticulous analysis,” Girish Kulkarni, a professor at the Department of Theoretical Physics at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, said. “It’s not so much a brand-new technique as careful work making the most of the observations.”

Prof. Kulkarni wasn’t involved in the study.

Too soon, too ready

Alaknanda’s existence poses a significant puzzle for astronomers.

“Current models suggest it takes billions of years for the stable, rotating disks necessary for spiral arms to form,” said Ms. Jain.

However, Alaknanda took shape when the universe was only about 1.5 billion years old, defying the current models of galaxy formation.

According to Prof. Kulkarni, understanding galaxy formation is a “complex system problem,” akin to predicting the weather or the climate. Unlike “simple” physics problems, where fundamental principles might be unknown, complex problems involve known principles but have too many interacting parts to be modelled perfectly.

“Current simulations don’t yield spiral galaxies with this degree of structure at z ~ 4, and when observations disagree with simulations, it usually tells us which ingredients need refinement,” Prof. Kulkarni said.

This means any mismatch is scientifically more useful rather than troubling.

(‘z ~ 4’ is a reference to the redshift, which is the stretching of light to longer wavelengths as the light source recedes from the observer, in this case the earth. The ‘z’ measures the fractional increase in wavelength.)

So how did Alaknanda manage to form a mature spiral disk in such a short time?

According to Ms. Jain, there are two theories about the formation of spiral arms. One is that the galaxy grew steadily by drawing in cold gas, allowing it to settle into a stable, rotating disk in which density waves could form and sustain the spiral patterns. The other is that Alaknanda interacted or merged with a smaller companion galaxy, causing the arms to form.

Even so, astronomers believe spiral arms would have needed more time to form in such a young universe.

“There could be some factor accelerating this process,” Ms. Jain said.

‘Robust findings’

Astronomers usually study galaxies in the distant universe using the energies of light they emit, which reveal the chemical composition and physical conditions in the galaxy. In the absence of such data, as in the new study, they measure the galaxy’s brightness at different wavelengths to reconstruct its overall energy distribution. This is called photometric analysis.

Jain et al. did this using data from the JWST. And with the reconstructed spectrum, they were able to estimate its redshift, stellar mass, and star-formation history.

Prof. Kulkarni said that while the study relied on photometric analysis, its findings appear robust as the team carried out three independent and consistent redshift measurements. However, he suggested the researchers also examine detailed spectroscopic data, such as JWST’s Integral Field Unit images, to ensure the observed structure isn’t caused by clumpy features and to confirm Alaknanda is truly spiral rather than a chance alignment.

The current observations are also insufficient to determine which of the two plausible mechanisms is responsible for Alaknanda’s arms. To this end the team plans to propose further observations with JWST or with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile.

Indian astronomy

Finally, the discovery of Alaknanda is also a significant achievement for Indian science. Prof. Kulkarni said India’s presence in major JWST discoveries has been limited by a smaller astronomy workforce, fewer dedicated training programmes, and lower funding compared to that in the bigger research economies, as well as less sustained participation in large international survey collaborations.

To catch up and then jump ahead, the Indian astronomy community is pursuing a two-pronged strategy: to build domestic facilities, like the proposed 10-metre optical telescope in Hanle, to train the next generation of scientists, and to join large, multinational projects like the Square Kilometer Array (SKA) and LIGO, which can guarantee access to world-class instruments.

Shreejaya Karantha is a freelance science writer.

Published – December 29, 2025 11:45 am IST