The Supreme Court of India’s November 20, 2025, ruling regarding the Aravalli range has ignited a firestorm across the country. The apex court accepted the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s elevation-based definition of the Aravallis.

The new definition states: “Any landform located in the Aravalli districts, having an elevation of 100 metres or more from the local relief, shall be termed as Aravalli Hills. For this purpose, the local relief shall be determined with reference to the lowest contour line encircling the landform. The entire landform lying within the area enclosed by such lowest contour, whether actual or extended notionally, together with the Hill, its supporting slopes and associated landforms irrespective of their gradient, shall be deemed to constitute part of the Aravalli Hills.”

Many critics have warned that the range, already suffering from the severe depredations of the illegal mining and real estate lobbies, could be history if the new definition becomes law. Several speakers have also pointed out the vital importance of the Aravalli range for northwestern and northern India.

But even as the debate is getting fiercer, all sides only need to go back a couple of centuries to know what the Aravallis were for one of Rajasthan’s most important personalities, a Scotsman by the name of Colonel James Tod.

From Britain to Rajputana

James Tod was born in London, England, in 1782 to parents of Scottish origin. It was in 1707 that England and Scotland had formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain, thus uniting the entire island (though Scottish nationalists want to secede from the union today).

After being educated in Scotland, Tod joined the British East India Company (‘Company Bahadur’ for us Indians). In 1799, he came to India, where the British were already a significant force by then.

But it was 19 years later that a development took place that was to cement Tod’s place in history. He was appointed as the British political agent for various princely states of western Rajputana in 1818. Rajputana is roughly analogous to the modern state of Rajasthan today.

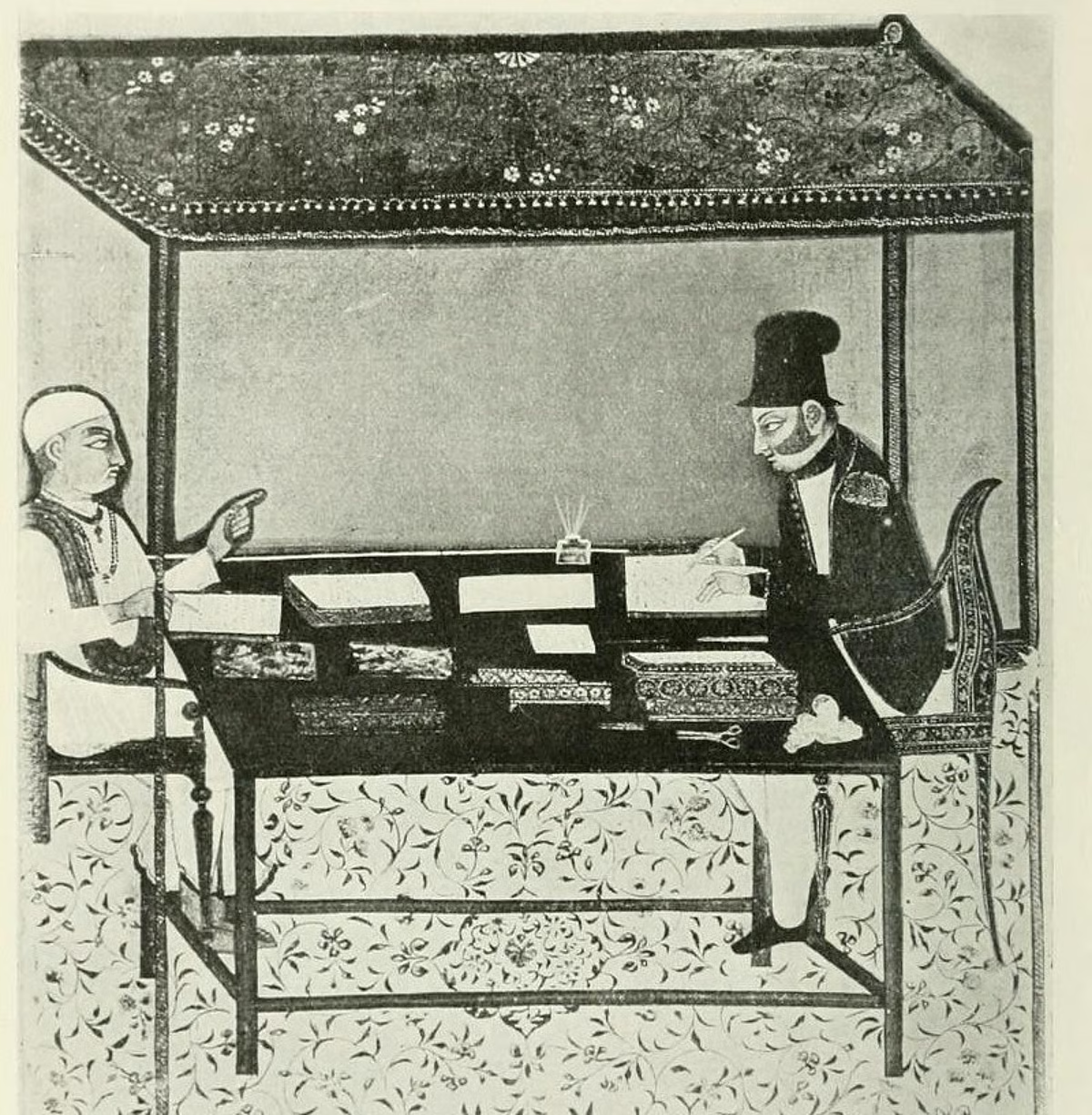

For 20 years, Tod lived among the Rajputs and other peoples of Rajputana. He observed them, studied them and finally documented what he had found. His work, Annals And Antiquities of Rajasthan Or The Central And Western Rajput States of India, which was published in two volumes in 1829 and 1832, introduced Rajputana/Rajasthan to the world, although the Annals also covered the current day states of Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh as well, which too had Rajput-ruled kingdoms.

What made Tod’s Annals unique is that it collated the existing scattered history of Rajputana and the Rajputs in the form of oral tradition and gave it a comprehensive and concise form. In this sense, Tod’s work was foundational.

No wonder then, he is often dubbed the ‘Father of Rajputana History’.

Tod on the Aravallis

Tod was mesmerised by the landscape of the Rajput kingdoms and his Annals gives ample evidence of this. Included in this are the Aravallis, at the core of the present controversy.

In a footnote, Tod tells us what we have been listening to ever since the controversy broke: that the Aravallis are some of the oldest landforms on our planet.

“Oldest of all the physical features which intersect the continent is the range of mountains known as the Arāvallis, which strikes across the Peninsula from north-east to south-west, overlooking the sandy wastes of Rājputāna. The Arāvallis are but the depressed and degraded relics of a far more prominent mountain system, which stood, in Palaeozoic times, on the edge of the Rājputāna Sea. The disintegrated rocks which once formed part of the Arāvallis are now spread out in wide red-stone plains to the east (IGI, i. 1),” he writes.

Tod also knows what news channels and media outlets have been breathlessly telling us in the last few days about the ‘barrier’ nature of the Aravallis in northwestern and northern India. He does this while describing the Marusthali, as the Great Indian or Thar Desert is known locally.

“Marusthali is bounded on the north by the flat skirting the Ghara; on the south by that grand salt-marsh, the Ran, and Koliwara; on the east by the Aravalli; and on the west by the valley of Sind. The two last boundaries are the most conspicuous, especially the Aravalli, but for which impediment Central India would be submerged in sand; nay, lofty and continuous as is this chain, extending almost from the sea to Delhi, wherever there are passages or depressions, these floating sand-clouds are wafted through or over, and form a little thal even in the bosom of fertility.”

Rich in minerals

Tod waxes eloquent about the geological nature of the Aravallis. He writes beautifully about how they are rich in granite and quartz.

“The general character of the Aravalli is its primitive formation: granite, reposing in variety of angle (the general dip is to the east) on massive, compact, dark blue slate, the latter rarely appearing much above the surface or base of the superincumbent granite. The internal valleys abound in variegated quartz and a variety of schistous slate of every hue, which gives a most singular appearance to the roofs of the houses and temples when the sun shines upon them. Rocks of gneiss and of syenite appear in the intervals; and in the diverging ridges west of Ajmer the summits are quite dazzling with the enormous masses of vitreous rose-coloured quartz.”

He also notes that “the Aravalli and its subordinate hills are rich in both mineral and metallic products;” and then proceeds to describe the wealth found especially in the kingdom of Mewar in the southeast of Rajputana (Udaipur, Chittorgarh and other districts today).

“The tin-mines of Mewar were once very productive, and yielded, it is asserted, no inconsiderable portion of silver: but the caste of miners is extinct, and political reasons, during the Mogul domination, led to the concealment of such sources of wealth. Copper of a very fine description is likewise abundant and supplies the currency; and the chief of Salumbar even coins by sufferance from the mines on his own estate. Surma, or the oxide of antimony, is found on the western frontier. The garnet, amethystine quartz, rock crystal, the chrysolite, and inferior kinds of the emerald family are all to be found within Mewar; and though I have seen no specimens decidedly valuable, the Rana has often told me that, according to tradition, his native hills contained every species of mineral wealth,” writes Tod.

The Apennines of India

Tod also thoughtfully compares the Aravallis to the Apennine mountains of the Italian Peninsula. Like their southern European counterparts, the Aravallis, for Tod, serve as a prominent natural boundary, demarcating the regions of western and central India.

“On reflection, I am led to pronounce the Aravalli a connexion of the ‘Apennines of India’; the Ghats on the Malabar coast of the peninsula: nor does the passage of the Nerbudda or the Tapti, through its diminished centre, militate against the hypothesis, which might be better substantiated by the comparison of their intrinsic character and structure,” writes Tod.

Maybe everyone arguing against each other in the fierce debate of today may as well read these words of one who first introduced this region to the world.