- In this interview with Mongabay-India, retired forest officer M.I. Varghese talks about the intent of forest laws, amendments, and the need for viewing local communities as partners in conservation.

- The Kerala Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Bill, 2025, shifts a scientific decision to the administrative hands, Varghese notes.

- He notes that institutional strength, independent boards and transparent public consultation, are important to strengthen conservation.

From the Himalayas to the Western Ghats, India’s forest and wildlife protection laws that prevented forest diversion, have been relaxed over the years for roads, mines, hydropower, defence infrastructure, and industrial corridors. Highways now run through elephant corridors and mining trucks move across tiger habitats. Encroachment by private lobbies, resort groups, and plantation operators, is often protected by political influence.

This scenario is commonly seen in the south Indian coastal state of Kerala. The state has introduced amendments to the Kerala Forest Act, 1961, and the Kerala Private Forests (Vesting and Assignment) Act, 1971. While officials say these amendments are meant to curb encroachment and protect farmers, environmentalists warn they may primarily assist powerful landholding interests seeking to legalise occupation in forest regions.

The Kerala Legislative Assembly has also passed the Kerala Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Bill, 2025, awaiting presidential assent. The Bill devolves powers to district collectors and junior forest officers to authorise lethal action during human-wildlife conflict. Conservationists fear this could normalise killing, undermine scientific wildlife management, and violate constitutional and international biodiversity commitments.

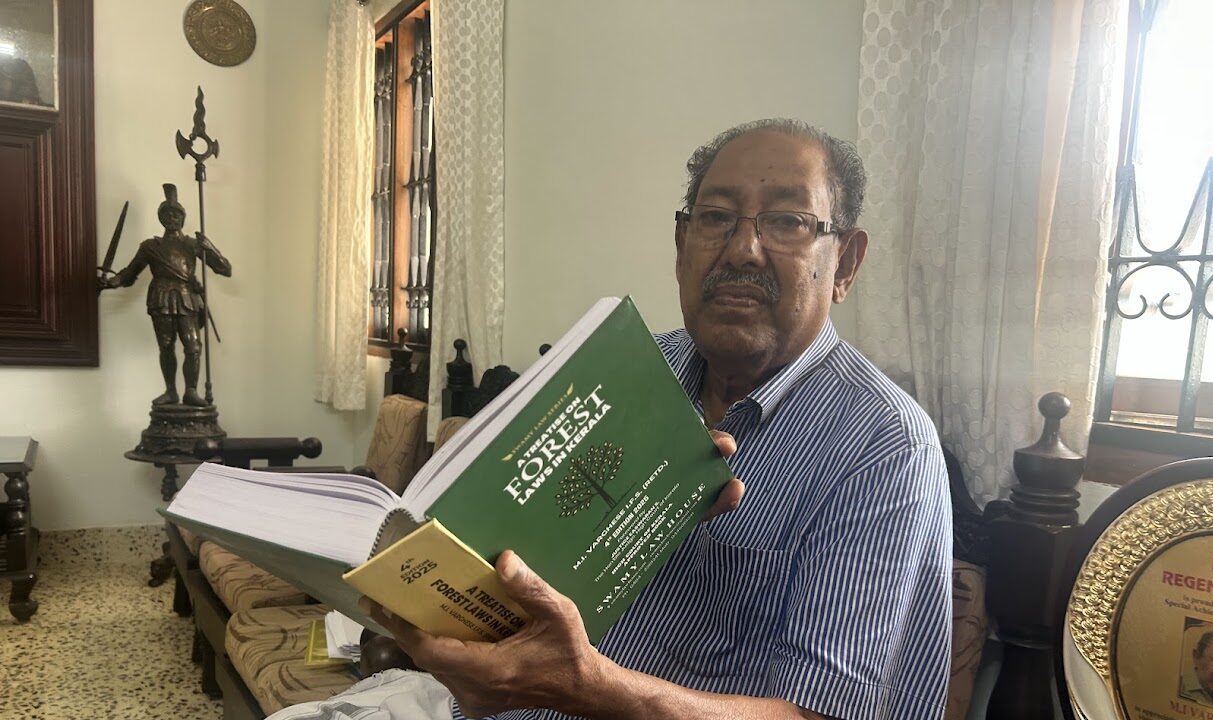

To understand these legislative shifts, Mongabay-India spoke to M.I. Varghese, a retired Indian Forest Service officer, legal scholar, and author of A Treatise on Forest Laws in Kerala. Varghese served across forest divisions in Kerala and spent decades interpreting environmental law. He reflects on the erosion of legal safeguards and the dangers ahead.

Varghese reminds us that forests cannot speak for themselves and that the law must be their voice. If that voice grows faint, the silence that follows will echo across generations, he says.

Mongabay: Having witnessed India’s conservation regime evolve since the 1970s, how do you view the trajectory from the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 and the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 to the current wave of amendments?

Varghese: The 1970s and 1980s marked a moral awakening. The Wildlife Act of 1972 responded to vanishing species, shrinking habitats and rampant poaching. The Forest Conservation Act of 1980 arose because states were diverting forest land without restraint. These laws introduced central oversight because states had failed to protect forests. The principle was that forests are national ecological assets rather than state revenue properties.

Today, the vocabulary is very different. We hear about ease of doing business and streamlining clearances. Behind those phrases is a steady rollback of checks and balances that once made conservation meaningful. Amendments expand exemptions and quietly redefine what counts as forest. The law has shifted from restraint to facilitation, from protection to legitimisation of diversion.

Mongabay: What, in your view, was the original moral and ecological intent behind these laws, and where did we start losing that sense of purpose?

Varghese: The original intent was ethical and constitutional. Articles 48-A and 51-A (g) bind the state and citizens to protect forests and wildlife. The judiciary deepened this through judgments that treated forests as part of the public trust held on behalf of future generations. Environmental protection became part of the right to life. We lost that moral centre when forests began to be seen primarily as impediments to development. Conservation was interpreted as management, which gradually became a euphemism for controlled exploitation. The language of ecology has been replaced by the language of economics. What is needed is a reaffirmation that these laws are not obstacles but instruments of collective survival.

Mongabay: Critics say the 2023 Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act effectively opens forest land to commercial, defence and infrastructure projects under new definitions. Do you see this as necessary modernisation or dilution (of the Act)?

Varghese: It is serious dilution. By changing definitions the amendment exempts large areas from central scrutiny, especially corridors, plantations and degraded forests which are still critical for biodiversity. The claim of balancing diversion with compensatory plantations is flawed. You cannot replace a natural forest with a plantation and call it restoration. Forest ecology cannot be reduced to arithmetic. This is not modernisation. It is regression presented as reform.

Mongabay: Many recent amendments claim to empower states and local authorities. Does this actually lead to improved conservation?

Varghese: Empowerment in this context weakens accountability. Central scrutiny was introduced because the state administrations were under pressure from powerful lobbies. If authority shifts to the same levels where misuse has historically occurred, we risk a race to the bottom. States will compete to appear investor friendly rather than forest friendly. True decentralisation means community participation and institutional involvement at the grassroots, not simply shifting a signature from Delhi to a state secretariat.

Mongabay: Courts have repeatedly upheld wildlife protection as part of India’s constitutional duties. Do you think the judiciary still plays a strong enough role as a check on dilution?

Varghese: The judiciary has been a refuge of environmental sanity. Landmark rulings from the Godavarman case, and onward treated forests as public trust assets. In the recent years there is some fatigue. Courts face pressure to balance conservation with development and the language is shifting toward sustainable use. Yet the judiciary remains the best defence we have. When the legislature dilutes and the executive capitulates, constitutional courts are essential for reminding us that ecological security is not negotiable.

Mongabay: The government says Kerala’s amendments will strengthen enforcement against encroachment while farmers fear criminalisation. Where does the balance lie?

Varghese: Encroachment is real but not uniform. There is a profound difference between organised land grabbers and families who have lived and farmed in forest fringes for decades. Drafting sweeping punitive provisions risks criminalising small cultivators while granting excessive discretion to officials.

Kerala’s first task is clarity. Forest boundaries remain uncertain in many places because mapping has been sporadic and inconsistent. Without precise maps every plot near a forest becomes suspect and conflict grows. Once clarity exists, long standing occupations should be treated humanely. Regularisation, conditional rights and relocation have been shown to work better than coercion. Conservation succeeds when communities are treated as partners rather than intruders.

Mongabay: The Kerala Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Bill, 2025 proposes to let district collectors and chief conservators permit the killing of wild animals. How does this square with the central Wildlife (Protection) Act?

Varghese: It does not square. Under the central Act the power to authorise killing rests with the Chief Wildlife Warden and only after all non-lethal measures fail. The Kerala amendment shifts a scientific decision to administrative hands. It also allows the state to declare certain species vermin, which is a power reserved for the Union Government. This undermines the constitutional framework and weakens the ethical and scientific foundations of conservation. Decisions about lethal action must be guided by ecology rather than convenience or local pressure.

Mongabay: If Kerala succeeds, do you fear other states could justify similar shortcuts?

Varghese: That is the danger. If one state sets this precedent others dealing with rising conflict will demand similar powers. Wildlife does not recognise political boundaries. Elephants move between Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Fragmenting legal authority will fragment conservation.

Mongabay: What role should and does scientific evidence play before any lethal intervention and are state agencies equipped for such assessments?

Varghese: Scientific evidence should be the foundation. Guidelines are clear that lethal action is the last resort. Unfortunately most states lack trained wildlife biologists and proper conflict documentation. Decisions are often made in haste and under pressure, based on anecdote rather than analysis. That is not science. It is improvisation.

Mongabay: How far do land use change, corridor fragmentation and human encroachment, drive rising conflicts?

Varghese: Almost entirely. Animals are moving because their habitats are fragmented. Plantations, quarries, highways and resorts have cut through corridors and dried up water sources within forests. We are fighting symptoms while ignoring causes. Conflict is a governance failure rather than a wildlife problem.

When land use planning ignores corridors, when quarrying continues inside buffer zones and when waste attracts wild boars, those are administrative issues. Conflict mitigation must be integrated into planning, agriculture and disaster management rather than placed entirely on the forest department.

Mongabay: Is there political interference in forest and wildlife management today?

Varghese: It is widespread. Decisions on transfers, appointments and clearances are often politicised. Institutional strength, independent boards and transparent public consultation are necessary for insulating conservation from populism. Without that, we will soon have forests in legal language only.

Mongabay: What reforms are urgently needed to modernise conservation law for the next decades?

Varghese: Conservation must be guided by ecological principles written clearly into law. There must be harmony between forest, wildlife and climate legislation rather than overlapping provisions and loopholes. Scientific institutions and statutory authorities must have real influence. Community consent and proper ecological assessment should be mandatory before forest diversion. Conservation begins in education and awareness, not only in statutes.

Mongabay: From your years of experience in the forest service, what do you consider India’s major ecological shortcoming, and where do you find hope?

Varghese: Our failure is in treating ecology as a sector rather than as the foundation of life. We have forgotten that forests are not obstacles but supports for civilisation. Yet, I remain hopeful. Young foresters still care, people protest mining in sacred groves and school children plant trees without instruction. Law may bend, but conscience can correct it if society remembers that protecting a forest is an act of patriotism.

Read more: Legal ambiguity hinders rewilding efforts in India

Banner image: M.I. Varghese, a retired Indian Forest Service officer, legal scholar, and author of A Treatise on Forest Laws in Kerala. Image by K.A. Shaji.