Cats have long been kept at American dairy farms to kill rats, mice and other rodents. In March 2024, a number of barn cats at dairies in the Texas panhandle started to behave strangely. It was like the opening scene of a horror movie. The cats began to walk in circles obsessively. They became listless and depressed, lost their balance, staggered, had seizures, suffered paralysis and died within a few days of becoming ill. At one dairy in north Texas, two dozen cats developed these odd symptoms; more than half were soon dead. Their bodies showed no unusual signs of injury or disease.

Dr Barb Petersen, a veterinarian in Amarillo, heard stories about the sick cats. “I went to one of my dairies last week, and all their cats were missing,” a colleague told her. “I couldn’t figure it out – the cats usually come to my vet truck.” For about a month, Petersen had been investigating a mysterious illness among dairy cattle in Texas. Cows were developing a fever, producing less milk, losing weight. The milk they did produce was thick and yellow. The illness was rarely fatal but could last for weeks, and the decline in milk production was hurting local dairy farmers. Petersen sent fluid samples from sick cows to a diagnostic lab at Iowa State University, yet all the tests came back negative for diseases known to infect cattle. She wondered if there might be a connection between the unexplained illnesses of the cats and the cows. She sent the bodies of two dead barn cats to the lab at Iowa State, where their brains were dissected.

Petersen’s hunch led to a series of important discoveries. The dairy cows in north Texas were suffering from highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) – and the barn cats had been infected with this virulent bird flu after being fed raw milk from the sick cows. H5N1 had emerged years earlier in Asia, travelled to the United States via migrating birds, and began to devastate US poultry farms in 2022. The fatality rate of H5N1 among poultry approaches 100% – and more than 150 millon chickens have been culled by American farmers since 2022 to halt the spread of this new virus. Researchers have known for years that cats were vulnerable to bird flu. In previous cases, they’d been sickened mainly by eating infected birds. But until Peterson’s discovery, nobody knew that cows could be infected with bird flu, that the virus propagated in their udders, and that it could be spread by their milk.

A commonsense response to the discovery of H5N1 among Texas dairy cattle in 2024 would have been mandatory testing of every cow for the virus, a strict quarantine of dairies where bird flu was found, mandatory testing of milk for contamination, monetary compensation to dairy farmers for any losses caused by the disease, and widespread testing of dairy workers to ensure that H5N1 was not spreading from cows to people. None of those things happened.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is primarily responsible for the health of livestock, not people. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has no authority to test livestock for diseases. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lacks the authority to test farm animals or farm workers without the permission of farm owners. State officials can wield those powers. But the Texas agriculture commissioner, Sid Miller, a rightwing conspiracy theorist who’d spoken at a QAnon event in Dallas a few years earlier, thought H5N1 posed “no threat to the public”. The dairy industry opposed the routine testing of its cows or workers – and dairy was responsible for about $50bn of economic activity in Texas every year. Miller made clear how he felt about federal investigators visiting dairies in the panhandle to look for bird flu: “They need to back off.”

Twenty-five years ago, my book Fast Food Nation outlined the dangers of a food system controlled by a handful of multinational corporations. As the book argues, the real price of cheap food doesn’t appear on the menu. The industrialisation of livestock, the transformation of sentient creatures into commodities, and the absence of government oversight have created new vectors for dangerous pathogens. Some American mega-dairies may have as many as 100,000 cows – and the enormous number of cows living in a single barn, the milking of numerous cows with the same equipment, the failure to impose quarantines and the interstate shipment of cows from one mega-dairy to another, enabled H5N1 to spread throughout the US.

During the past 30 years, the dairy industry in the UK has become far more dependent on large-scale production and grown remarkably centralised as well. In 1980, there were 46,000 dairy farms in the UK. Now there are just over 7,000. Just four companies now process about 75% of the UK’s milk.

Changes in the size, scale, and structure of the dairy industry have also led to changes in the workforce. Today’s American dairy workers are likely to be recent immigrants who are paid low wages. They sometimes work 60 to 80 hours a week, and often move around frequently between jobs.

The first person to be infected with H5N1 in the US was a dairy worker in Texas. A few weeks after the discovery of bird flu in cows, the worker developed an unexpected symptom of the disease: pink eye. Testing found that the conjunctivitis was caused by H5N1. Otherwise, his illness was mild. He didn’t develop upper respiratory congestion or a fever and recovered fully within a few days. Despite the possibility that H5N1 might be silently spreading among dairy workers – and the risk that it could mutate inside a human host to become lethal to humans and highly contagious – few workers were tested for H5N1. The dairy industry opposed testing them, and immigrant workers were reluctant to have any interaction with state or federal investigators, fearing deportation.

The first known human cluster of H5N1 infections in the US occurred among poultry workers in Weld County, Colorado, during July 2024. Weld County now has poultry farms, egg farms and mega-dairies – in addition to the vast cattle feedlots and the beef slaughterhouse described at length in Fast Food Nation. Workers often move from job to job at these industrial-scale operations. At one of the largest egg farms in Colorado, not far from Greeley, a group of workers was instructed to cull hens that had tested positive for H5N1. The workers spent hours in hot, poorly ventilated henhouses, killing almost 2 million birds and collecting their bodies for disposal. Five workers later developed fevers, chills, upper respiratory symptoms and pink eye. It was the largest human outbreak of bird flu in American history.

None of the workers were hospitalised, and all soon recovered. But their illnesses suggested that mild or even asymptomatic cases of bird flu might be occurring among workers at poultry farms, egg farms and dairies throughout the US. As more workers and more cows became infected, the risk of a dangerous mutation in the virus increased. When the Weld County cluster occurred, roughly four months had passed since the first Texas dairy worker had been sickened by bird flu – and yet only 200 workers had been tested for H5N1 nationwide.

Bird flu is a zoonosis – an infectious disease that can be transmitted from vertebrate animals to human beings. Like E coli O157:H7 (which emerged in cattle feedlots) and methicillin-resistant S aureus (also known as MRSA, which emerged at industrial hog farms and kills about 9,000 Americans every year), H5N1 is simply the latest unanticipated cost of factory farming.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) has not yet caused a deadly epidemic among human beings. Pasteurisation kills H5N1 in milk, and the virus hasn’t mutated to become more contagious or more lethal. But H5N1 has become endemic among wild birds, chickens, turkeys and dairy cattle in the US, allowing a continual mixture of its genes. A bird flu epidemic that kills millions of people may never emerge from factory farms – or it may next week, next month or next year. The threat is global. On 9 December, H5N1 was confirmed among poultry at a large factory farm in Lincolnshire in the UK. A two-mile exclusion zone was put in place and all the birds on the premises were to be culled. It was the second confirmed outbreak in a week.

When Fast Food Nation was published in January 2001, I didn’t expect the industrial food giants to like it. And they did not like it. The book reveals how they operate, looking at the great discrepancy between their slick marketing and the reality of their business practices. It describes the impact of the industrial food system on workers, consumers, farm animals and the environment.

“The real McDonald’s bears no resemblance to anything described in [Schlosser’s] book,” a statement from the McDonald’s Corporation said. “He’s wrong about our people, wrong about our jobs, and wrong about our food.” The National Restaurant Association said: “In addition to acting like the ‘food police’ and trying to coerce the American consumer never to eat fast food again, [Schlosser] recklessly disparages an industry that has contributed tremendously to our nation.”

A spokesperson for the American Meat Institute claimed that my evidence of safety problems in meatpacking plants was “anecdotal” and that I’d “vilified the industry in a way that is very unfair”. The Heartland Institute, a rightwing thinktank, later said that I was “tricking young people … to lead them away from capitalism into his failed socialist ideology”. According to the Wall Street Journal, McDonald’s later hired the DCI Group – a “strategic public affairs consulting firm” with strong links to the oil, tobacco and pharmaceutical industries – to post online attacks on me. (McDonald’s denied using third parties to attack me and said they “appreciate feedback”.)

Despite the personal attacks, none of the book’s industry critics cited factual errors in it. More surprising were the disruptions that occurred during my public appearances to talk about food issues. At different events in different cities, I’d often get exactly the same hostile questions, as though they’d been scripted in advance. Protesters interrupted my talks, threats were made against me. Armed security guards sometimes stood beside me when I signed books, and during a visit to a university in Indiana, I was accompanied in public by a state police officer from the time I landed at the airport in Indianapolis until the time I left the state a few days later. After a panel discussion in Tucson, I was assaulted in the parking lot by a man who got me in a headlock and shouted at me: “Why do you hate America? Why do you hate America so much?” It was a bizarre, unsettling experience.

What happened to me was trivial compared to the pushback other fast food industry critics have experienced. In 2008, Burger King hired a private security firm to infiltrate the Student/Farmworker Alliance – a nonviolent group – that was urging consumers to boycott Burger King because some of its suppliers were linked to slave labour in the tomato fields of Florida. The owner of the security firm, Diplomatic Tactical Services, posed as a college student to collect information for Burger King. She did a poor job of impersonating a young activist and aroused suspicions. She was soon outed as a corporate spy, creating some bad publicity for Burger King.

The McDonald’s Corporation was much more successful at spying on its critics. During the 1980s, sometimes half the people attending London Greenpeace meetings were corporate spies hired by McDonald’s to collect information on the group. As the Guardian journalist Rob Evans has chronicled in depth, Scotland Yard had also infiltrated London Greenpeace with undercover agents. The corporate spies and undercover police officers helped McDonald’s to gain an advantage in the McLibel case, a lawsuit directed at two members of London Greenpeace. While pretending to be an anti-McDonald’s activist, one of the undercover police officers had a romantic relationship with a member of London Greenpeace for almost two years, while secretly collecting information on her. And one of McDonald’s corporate spies slept with a different Greenpeace activist for about six months, also as a way to build trust and gain information. An inquiry into the conduct of more than 139 undercover police officers who spied on tens of thousands of activists between 1968 and 2010 is now in progress.

“The history of the 20th century was dominated by the struggle against totalitarian systems of state power,” I wrote in Fast Food Nation. “The 21st will no doubt be marked by a struggle to curtail excessive corporate power.” Well, at least I got it half-right. We now have to struggle against both.

One of the book’s central aims was to reveal how private interests were being served at the expense of the public interest. The workings of the industrial food system amply illustrated those larger themes. An investigation of the banking, aerospace, chemical, defense, healthcare, entertainment or software industries would have reached similar conclusions.

Consumers now possess merely an illusion of choice. The corporate mergers and acquisitions of the past four decades have greatly reduced the number of companies that sell food, a fact hidden by the multiplicity of brand names. For example, Starbucks is the largest chain of coffee shops in the world. But a family-owned German firm, JAB Holding Company, sells more coffee than Starbucks does, under multiple brand names that JAB wholly or partially owns – including Keurig, Krispy Kreme, Peet’s Coffee, Stumptown Coffee, Green Mountain Coffee Roasters and Pret a Manger.

When large corporations gain too much power, the prices offered to suppliers, the wages paid to workers and the prices charged to consumers are no longer driven by market forces. Government agencies become “captive” to the companies they’re supposed to be regulating. And those corporations earn higher profits by lowering wages, raising prices and manipulating supplies. When four companies gain a combined market share of 40% or higher, competition readily gives way to collusion. What was once a free market becomes an oligopoly.

Today, four companies control 56% of the worldwide market for seeds and 61% of the market for pesticides. Five companies control about 70% to 90% of the worldwide trade in grains. Four companies control more than 80% of the US supply of beef, 70% of its pork and 60% of its market for chicken. Four companies control about 75% of the US market for yoghurt, 79% of its market for beer. Three firms control 93% of its market for carbonated soft drinks. Factory farming has extended monopoly power even to commercial-livestock genetics. Two companies provide the breeding stock for more than 90% of the world’s egg-laying hens and turkeys.

Hidden market power can suddenly be revealed when something goes wrong. During the summer of 2024, an outbreak of E coli prompted a massive precautionary recall of sandwiches from stores and supermarkets throughout the UK. Hundreds of people were sickened; two died. A report by the UK Health Security Agency later said that “epidemiological analyses provided robust evidence that pre-packaged sandwiches containing lettuce were the likely vehicle of infection”. The lettuce was the probable source of E coli. Although never conclusively linked to any specific sandwich company or brand, the outbreak was illuminating about how our food is now prepared. Many of the recalled items were made by the same firm: Greencore, perhaps the world’s largest manufacturer of fresh, pre-made sandwiches.

Based in Ireland, Greencore sells about 600m sandwiches a year in cardboard packages bearing the logos of other brands, such as Boots, Marks & Spencer, Sainsbury’s, Tesco and WH Smith. A video taken at a Greencore factory in Nottinghamshire, England, shows hundreds of workers standing at assembly lines in a gigantic refrigerated room, wearing white coats and green hairnets, adding ingredients by hand as slices of bread pass them on conveyer belts. The factory runs 24 hours a day and makes hundreds of different kinds of sandwich. The familiar little packages that contain these sandwiches – lined up in refrigerated display cases at grocery stores, petrol stations and airport newsstands – offer no hint that what’s inside them was assembled on an industrial scale.

A much more serious form of hidden market power was revealed when an infant in Minnesota became ill with Cronobacter sakazakii during the fall of 2021. Cronobacter is a pathogenic bacteria that can be dangerous to infants who are younger than two months, born prematurely or immunocompromised. After an infection with Cronobacter, the estimated death rate among these babies ranges from 40% to 80%. Many who survive have lifelong brain damage and seizure disorders. The baby sickened in Minnesota was hospitalised for three weeks but survived. Three more infants were soon diagnosed with Cronobacter in other states. Two of them died. All the illnesses were linked to powdered infant formula manufactured at the same plant: one of the largest infant formula factories in the US, occupying 800,000 sq feet and covering more land than a dozen football fields. The plant was located in Sturgis, Michigan, and owned by Abbott Nutrition.

When inspectors from the Food and Drug Administration visited Sturgis early in 2022, they found multiple strains of Cronobacter in the Abbott factory. FDA officials later described conditions at the plant as “shocking” and “egregiously unsanitary”. Abbott voluntarily shut down the plant and recalled three brands of powdered formula made there. Abbott insisted that government investigators couldn’t find any evidence “to link our formulas to these infant illnesses”. But Frank Yiannas, who served as deputy commissioner of the FDA during the recall, thought that Abbott’s denials were misleading. “Abbott’s Sturgis facility lacked adequate controls to prevent the contamination of powdered infant formula,” Yiannis testified before Congress, “And it is likely that other lots of [powdered formula] produced in this plant were contaminated with multiple C sakazakii strains over time, which evaded end-product testing, were released into commerce, and consumed by infants.”

The Abbott factory in Sturgis produced about one-fifth of all the infant formula consumed in the US. When the Sturgis plant shut down and didn’t fully reopen for six months, parents scrambled to find infant formula amid nationwide shortages, hoarding and panic-buying that lasted throughout 2022. Monopoly power had greatly diminished the resilience of the food system, creating the risk that some babies might not be able to eat. At the time of writing, the market for infant formula in the US is still controlled by the same four companies. In the UK, the infant formula market is even more concentrated: one company, Danone, controls about 71%.

In many respects, the harms of the food system have only got worse during the 25 years since Fast Food Nation was first published. The consumption of ultra-processed foods – that is, most fast foods – has been linked to at least 32 health problems, including heart disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity and mental health disorders. More than half of the foods that Americans now eat are ultra-processed.

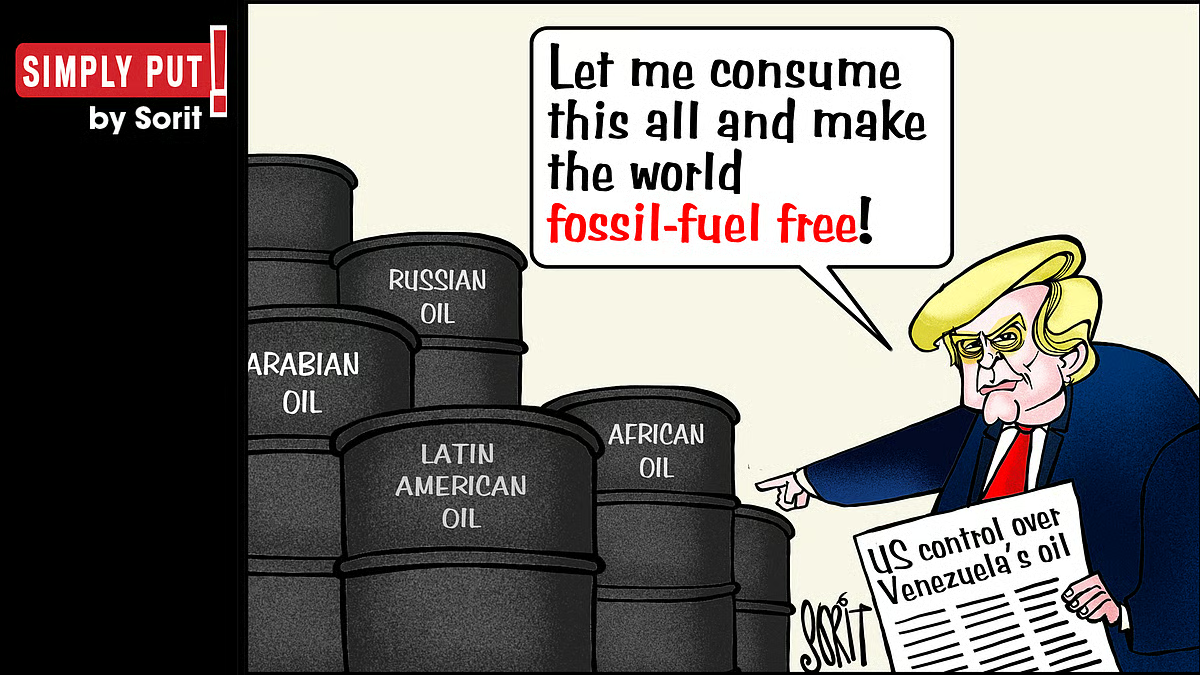

But there are still grounds for hope, as this mind-blowing tweet from President Donald Trump suggested, a week after his re-election in November 2024: “For too long, Americans have been crushed by the industrial food complex … [that has] engaged in deception, misinformation and disinformation when it comes to public health.”

If a politician who drinks 12 Diet Cokes a day, serves McDonald’s food at the White House, stages campaign events at McDonald’s restaurants – and routinely orders a meal of two Big Macs, two Filet-O-Fish sandwiches and a chocolate shake just for himself – now feels the need to criticise industrial food, a seismic shift has occurred in US popular opinion.

Some passages of The MAHA Report, issued by the Trump administration in May 2025, feel almost hallucinatory. A conservative Republican administration released a report condemning ultra-processed foods, calling for bans on synthetic food additives, lamenting the high obesity rate among American children, attacking federal agencies for their “corporate capture and the revolving door”, and placing some of the blame on “consolidation of the food system”.

The real significance of the Make America Healthy Again (Maha) crusade is the overwhelming popular support behind it. An opinion poll conducted by a conservative thinktank in 2025 found that 96% of probable US voters somewhat or strongly agreed that warning labels should be placed on ultra-processed foods containing additives linked to serious health risks – and the proportion of Republicans who agreed was 97%. In addition, 70% of probable voters opposed serving school meals that contain potentially harmful ultra-processed foods, and 95% supported requiring schools to serve fresh fruit and vegetables at lunch.

The idealism and passion of the Maha movement belies an ugly truth: the Trump administration has launched a radical assault on the government agencies devoted to food access, food safety and public health.

The mass firings and termination of longstanding programs by Donald Trump’s secretary of health and human services, Robert F Kennedy Jr, have been unprecedented. At the time of writing, the CDC has lost about one quarter of its employees. Its National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion may lose all of its funding to address heart disease and stroke, obesity, diabetes and many other disorders. Cuts to the CDC’s Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network mean that outbreaks of food poisoning in the US will soon be much harder to detect – which will only benefit companies that sell contaminated food. And a $590m grant awarded to Moderna for the development of a bird flu vaccine has been cancelled.

But all is not lost. We have agency in this world, for better or worse. In recent years, a new discipline has arisen that looks at economic activity from a system-wide perspective: true-cost accounting. It tries to measure the real costs that prices don’t always reflect. Applied to the food system, it incorporates the health, environmental and other externalised costs that businesses too often succeed at making everyone else pay. True-cost accounting makes clear that cheap, industrial fast food is actually far more expensive than we can afford.

According to a true-cost study by the Rockefeller Foundation, Americans spent $1.1tn on food in 2019. But that spending didn’t include the healthcare costs of food-related illnesses or the obesity epidemic, the food system’s contribution to air and water pollution, the social costs of the food system’s low-wage workforce or the costs of greenhouse gas emissions and reduced biodiversity. When those externalised business costs are added to the $1.1tn in spending, the true cost of what Americans pay every year for their food is closer to $3.3tn. The accuracy of that estimate can be disputed. It’s hard to assign a dollar value to natural capital such as a beautiful rural landscape that’s been bulldozed to make factory farms. How can you put a price on that sort of loss? But the underlying idea behind true-cost accounting is sound. The harms and benefits of our food system are unequally distributed.

Changing the economic incentives can lead to a huge change in real-world outcomes. As the environmental movement learned long ago, when polluters have to pay for their pollution, the air and water get cleaner. If a packet of ground beef had to include a list on the label of all the dangerous pathogens in the meat, market forces would reward companies devoted to food safety. The companies willing to sell tainted meat would have to lower their prices significantly or clean up their act.

In 2019, the food policy group Eat and the medical journal the Lancet issued a report, Food in the Anthropocene, linking unhealthy diets to the environmental damage caused by the industrial food system. It has become one of the most widely cited, peer-reviewed scientific papers of the past 20 years. The report argues that changing what we eat and how we produce it is essential not only for our own health but for the health of the planet.

Changing this system won’t be easy, and it may take years. But it’s been done before – child labour was once routine in US factories, until banned by the US supreme court. And the alternative to changing things will be a hell of a lot worse. So it must be done. When the disinformation, misinformation and lies of the Trump administration become undeniable, when the harms of its policies become inescapable, opportunities will arise. The same is true everywhere industrial, ultra-processed food is sold. After spending three decades investigating this fast food nation, I feel grateful for the friends I’ve made, inspired by the workers and farmers and ranchers and activists I’ve met, humbled, disappointed, amazed, outraged, angry beyond words – and yet hopeful.

Adapted from the 25th anniversary edition of Fast Food Nation: What the All American Meal is Doing to the World, published by Penguin Modern Classics on 29 January. To support the Guardian, order a copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply