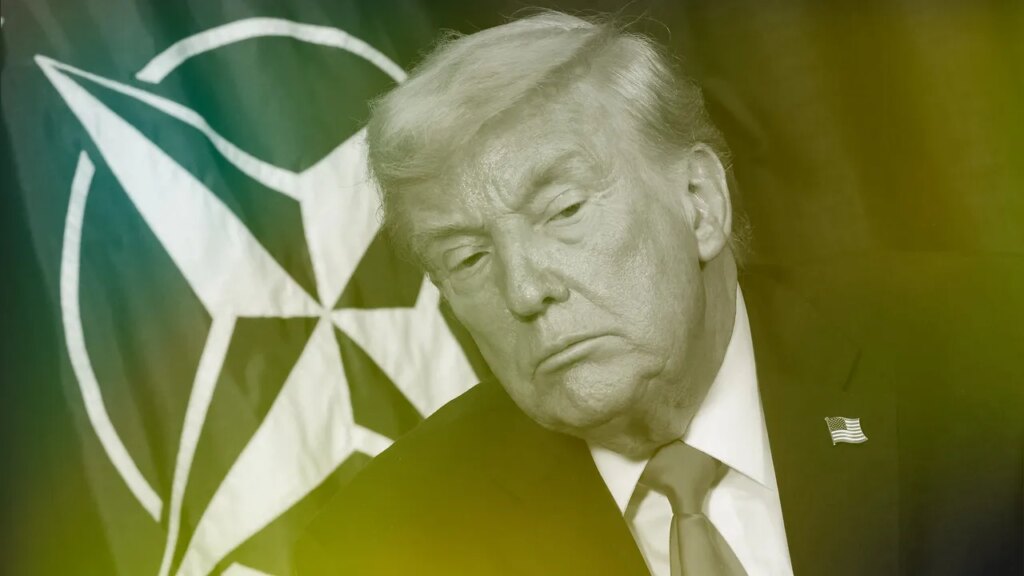

To be sure, the sudden drop in the dollar, by itself, “isn’t large enough to break anything,” as Setser put it. And on Friday the U.S. currency recovered some of its recent losses after Trump nominated Kevin Warsh, an experienced Republican banker, to replace Jerome Powell as the chair of the Federal Reserve. The market’s immediate reaction reflected a perception that Warsh is an inflation hawk and that his influence at the Fed could bolster the dollar. That remains to be seen, though. In auditioning for the job, he told Trump that he favored lower interest rates, which is what the President wanted to hear. If Warsh came to be regarded as a yes-man for Trump, that would be very negative for the dollar. More generally, the fear is that currency weakness could feed on itself if foreign investors lose faith in U.S. economic stewardship. Not only is Trump undermining NATO and using tariffs coercively, Prasad pointed out to me, but he has also spent twelve months attacking many of the domestic pillars of U.S. economic might, including the rule of law, the system of checks and balances, and the independence of the Fed.

For many decades, the U.S. dollar’s status as the dominant global currency was largely unchallenged. Foreign financial institutions and central banks built up large positions in U.S. financial assets, partly because they generated high returns and partly because they were widely viewed as a safe haven in an unsafe world. Right now, European countries are the biggest investors in America, holding an estimated eight trillion dollars in U.S. stocks and bonds. These investments help to finance the U.S. trade deficit and the U.S. budget deficit, both of which are very large. In the nineteen-sixties, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, France’s finance minister (and subsequently its President), described the capacity of the United States government to attract large amounts of foreign money at low rates as an “exorbitant privilege” that enabled the country to live beyond its means. The privilege has endured. But, as Trump was issuing thinly veiled threats to invade Greenland, George Saravelos, the global head of foreign-exchange research at Deutsche Bank, Germany’s largest bank, suggested, in a note to clients, that these moves might make European investors less willing to accumulate U.S. financial assets and help America finance its dual deficits. “In an environment where the geoeconomic stability of the western alliance is being disrupted existentially, it is not clear why Europeans would be as willing to play this part,” Saravelos wrote.

For a country that has more than thirty trillion dollars of debt, and which ran a budget deficit of nearly $1.8 trillion last year, any indication that foreign investors may hesitate before buying more of its assets cannot be taken lightly. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who was also in Davos, announced in an interview that the C.E.O. of Deutsche Bank, Christian Sewing, had called him to say that the bank, which has a large U.S. operation, didn’t stand by Saravelos’s report. But Saravelos himself hasn’t disowned his pessimistic analysis, and for good reason. Ultimately, the supremacy of the dollar rests on U.S. economic hegemony and trust in the American government, which Trump is busy eroding.

At this point, it’s not entirely clear who has been selling dollars. “The price action is consistent with European institutions reconsidering whether they want to keep adding to their U.S. assets,” Setser said. “It’s also consistent with fast money”—hedge funds and other speculators—“anticipating this trend and front-running it.” In the markets, betting against the dollar is known as the debasement trade. By early last week, the currency had fallen far enough for a political reporter to ask Trump, whether it had gone too far. “No, I think it’s great,” he replied. “The dollar’s doing great.” These comments prompted further selling, and the currency hit a four-year low. As often happens, Bessent was left to explain away his boss’s remarks. He appeared on CNBC the following day and insisted that “we have a strong dollar policy,” and argued that, over time, Trump’s tax cuts and tariffs would lead to more money coming into the United States and greater dollar strength.

Such an outcome isn’t inconceivable. Since the global financial crisis of 2007-09, the U.S. economy has grown faster than other major advanced economies; this has made it even more attractive to overseas investors. If, in the coming months and years, A.I. delivers the boost to G.D.P. and productivity which its promoters say it will, this U.S. outperformance could persist, or even quicken, and the dollar could rebound as Bessent predicted.