Hannibal Lecter’s first movie appearance was in 1986’s Manhunter, starring Brian Cox. It took director and writer Michael Mann just five weeks to adapt Thomas Harris’s novel Red Dragon for the screen.

But when it came to adapting his own work – Heat 2, co-authored with Meg Gardiner as both a prequel and sequel to his 1995 film Heat – Mann discovered the pain of self-editing. “I thought OK, 10 weeks, 12 weeks,” he reflects in a Zoom interview from Los Angeles. “Instead, it took like 10 months and it was arduous because I wanted the same effect as the novel, which required recombining events to fit within a two-and-a-half-hour timeframe. That selection became agonising to say the least.”

According to media reports, Heat 2 will have a $150m budget after moving from Warner Bros to United Artists with a cast rumoured to include Christian Bale and Leonardo DiCaprio. Mann remains both tight-lipped and cautious. “Listen, no picture happens until it’s happening, but right now we’re looking to start August 3,” he says.

For Heat devotees, it has been a long wait. When the three-hour crime epic was released 30 years ago this month, the film industry was in different place. Blockbuster Video ruled the roost, Netflix did not exist, CGI was expensive and rare while AI was mostly the realm of science fiction. The big hits at the box office were Toy Story, Apollo 13, Die Hard With a Vengeance and GoldenEye.

Notably, a report about Heat 2 on Deadline stated: “Filming in California for 77 days, Mann’s movie has projected it will hire 40 main cast members, 800 ‘base crew members’ and 1,350 background actors (not a lot of AI there).”

It was a small but telling reminder that Mann is a Hollywood artisan, a traditionalist who graduated from the London Film School in 1967 and whose work contains a kinetic authenticity. But now AI is on the march, capable of generating convincing video. It was a bone of contention during a historic labour dispute in 2023 that achieved some AI protections, though some artists were unhappy with the deal.

Mann comments: “Everybody’s very concerned and interested in what’s possible with AI, from a very cautionary perspective among the Screen Actors Guild, Writers Guild and Directors Guild because it may turn into a new kind of performance.

“Well, that performance has to be acted by an actor, written by a writer, and directed by a director regardless of whether the execution is from artificial generative intelligence or not. The other thing is that at the same time one observes that technology never goes backward. Then there’s issues of copyright ownership in which the studios are pretty much aligned with the creators like myself and other writers and actors and directors.”

Recent upheavals have seen Disney buy fellow studio 21st Century Fox, Paramount merge with Skydance Media and, most recently, the streaming giant Netflix agree to buy Warner Bros in an $83bn deal that still faces various obstacles, including a hostile takeover bid from Paramount. Some observers fear that victory for Netflix would result in fewer films gaining a theatrical release.

“Unless someone has a crystal ball, there’s no way to know the outcome,” says Mann, “I know what I’d like the outcome to be but I’m hardly in the inner circle. I know [Netflix CEO] Ted Sarandos but I don’t know their thinking.

“A more relevant question from an audience perspective is: what’s the inherent logic? The inherent logic is that, when you have a film like the new Avatar with Imax presentation or great Dolby laser with a fantastic sound system, people will come, they will flock to it. Is the pattern three years from now that the exhibition relies on becoming even more experiential, similar to concert venues?”

Mann is a creature of cinema who has described Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove as a formative influence on his career. “I make films for a large presentation,” he adds.

“My ambition is to very strongly and effectively impact the audience with the story with all the tools at my disposal to transport them into this world for two, two and a half hours. That’s what I’ve always wanted to do since I was in film school in London and so it’s a diminution for any of my – or any number of other directors I can think of – to have our films be seen 16-by-9 on an iPhone. The full power of performance and expression is what I make films for.”

Heat, released on 15 December 1995, is a case in point. Set in Los Angeles, the film follows the parallel lives of a master thief, Neil McCauley, and a dogged detective, Lt Vincent Hanna, whose private life is equally dysfunctional.

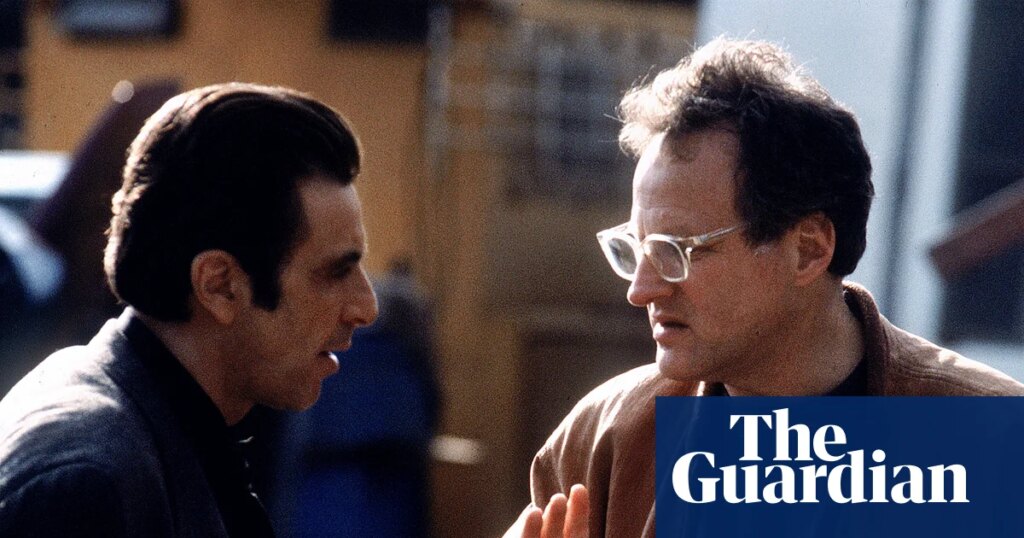

A key reason it has endured is the casting of Robert De Niro and Al Pacino as the opposite and equal protagonists. Mann recalls the idea came up over breakfast with his co-producer Art Linson. “I said, ‘Let’s think about who would be in it’; we said, ‘What about Bob, what about Al?’

“It was an automatic ‘it’s a fantastic idea’. I mean, the two greatest actors of their generation! The intensity, the internal power that De Niro has and the exuberance, the ability for performance with which Al could imbue a character, because within the character of Hanna, there’s a certain burlesque he uses with informants to keep them off balance, because in real life all informants lie some of the time. So it’s a constant game to manage an informant, to keep him off balance, to get the information you want.”

The cast also includes Val Kilmer, Jon Voight, Amy Brenneman, Ashley Judd and Diane Venora. Heat’s plot is based on the experiences of Chuck Adamson, a celebrated Chicago detective who hunted and eventually killed the real life Neil McCauley, a career criminal who had served eight years on the prison island of Alcatraz. Adamson became a friend and consultant to Mann.

The director recalls: “He had great respect and regard for McCauley professionally. If you’re the kind of driven detective that Adamson was, it’s like being a rock climber and your aspiration is to free climb Half Dome. So the better the crew you’re working, the bigger the challenge.

“He had a high regard for McCauley’s professionalism but also there was a certain discovered rapport between them because it was as if McCauley viewed aspects of life and how he modulated himself similarly to Adamson.

“They were both supremely self-aware, disciplined, fully conscious people, nearly devoid of self-deception. At the same time, in an encounter, each would blow the other out of his socks without thinking twice about it. That was the attitude.”

In 1963, Adamson spotted McCauley at a Chicago deli. Instead of arresting him, he invited him for coffee. Much of the dialogue in the film’s pivotal scene was taken directly from Adamson’s recollection of that meeting. Both men acknowledged they were professionals on opposite sides and that if they met again “around the corner”, they would have to kill each other.

Heat’s dramatisation of that meeting in a diner marked the first time that De Niro and Pacino were together on screen, despite both being in The Godfather Part II but in separate time periods. They did not rehearse the scene, a decision made at De Niro’s suggestion to keep the tension genuinely fresh.

Mann recalls: “That’s the pivotal moment, the nexus of the drama – and we all knew it. We discussed the scene, analysed the scene, even maybe paraphrased it a little in gentle discussion because we wanted complete understanding of the multiplicity of motivations behind each character’s wanting to observe each other, take in each other. Both characters knew that they’re subconsciously getting an intuitive sense of the opposite number because they’re likely to be in a confrontation.

“Both have lethal intent. What they don’t expect but do discover is the rapport when they start talking about their private lives and Hanna talks about a dream he has of dead bodies sitting around the table staring at him with eight-ball haemorrhages from gunshot wounds. Then De Niro asks: ‘What do they say?’ Al says, ‘Nothing.’ They don’t talk.

“Then De Niro expresses a dream about drowning, which basically translates into: does he have enough time for what he wants in life? It becomes very intimate – the intimacy of strangers. You don’t want to rehearse a scene like that. Everybody understands that the magic of one or two unique takes will happen and we all want that to happen spontaneously on camera, not in a rehearsal.”

Another indelible scene is a downtown shootout with a gritty, visceral quality that AI would struggle to replicate. McCauley’s gang successfully rob a bank but have been betrayed and are ambushed. Facing massed ranks of police, they try to shoot their way out.

Mann hired former SAS operatives Andy McNab and Mick Gould to train the cast in realistic firearms handling. “We blocked out here’s how this ambush would happen and here’s how they would react and assault it.

“When I found the location in downtown LA, I blocked the choreography across two city blocks. They’re leapfrogging: one guy’s laying down rounds while the other is moving forward and, then, he lays down rounds, et cetera, and it keeps going. We trained at the LA county sheriff’s shooting ranges under appropriately rigid safety procedures and sheriff’s range masters.

“The guys trained three days a week, mornings, for months to get that good. They could probably outshoot 95% of the [Los Angeles police department]. You discover very quickly as a director that actors have tremendous eye-hand coordination and a learning curve that’s like a hockey stick.”

He adds: “For the actors, they were living it and were using full-load blanks during the filming, which reverberated off the glass walls of the urban canyons we were in. The initial sound of the rehearsals was so frightening that I threw maybe 10, 11 mics around the location and so we wound up using the sound recorded during the filming.

“Traditionally the sound effects designer would build 60–70 tracks and you’d post-produce during three days of pre-dubbing the sound effects. I had an excellent sound designer, Lon Bender, but I discarded most of it and basically used the sound from the dailies.”

Heat ends with Hanna chasing McCauley to a vast, open field adjacent to the Los Angeles international airport runways. The setting is dark and industrial but periodically flooded with blinding light from passing planes and strobing runway markers. The two men play a high-stakes game of hide-and-seek among massive shipping containers and electrical boxes.

Mann recalls: “I wanted to leave the audience in a kind of – to use a music analogy – fugue state because you empathise with McCauley and want him to get away with [his girlfriend] Eady. Then with Hanna you’re empathetic to his pursuit of McCauley. There’s no compromise between the two states. I worked to have both there at 100% in what is fated to be a lethal confrontation between the two from which only one would survive.”

As a plane approaches for landing, the landing lights illuminate the field. McCauley prepares to ambush Hanna but, as he moves, the shifting lights cast his shadow on the ground in front of him. Hanna spots the shadow, whips around and fires first, killing McCauley.

“Then there’s the grace note where Hanna holds his hand, recalling the parallel between them, almost as if McCauley is fortunate to ride into death in tactical contact with one of the only other people on the planet who understands him. That counterpoint is how I wanted to leave it and that tends to sustain in memory.”