- In 2025 Mongabay-India reported about several new-to-science species.

- From sea butterflies and deep-sea squids to Himalayan bats, these species were described by scientists after several analyses which are time-consuming.

- By learning more about new species and their role in the ecosystem, we know how to protect them better.

In 2025 Mongabay-India reported about several new-to-science species. It takes several months or even years for researchers to confirm the new species description through morphological, DNA, taxonomic, environmental, phylogenetic assessments, and more. However, the stories we published this year about new species are small reminders that we have so much more to learn and understand about the biodiversity around us. Only by knowing more about them, can we learn how to protect and conserve them better.

Here are some of the species that got the staff and our readers very curious about the creatures we live among!

A fungus that can hold the weight of a person

All fungi silently work to maintain our ecosystems. Without them our forests will be full of debris, logs and leaf litter left undecomposed. But we know so little about the fungal diversity in India.

A recent discovery brings them to the spotlight as a ‘colossal’ new species has been described in Arunachal Pradesh. Arvind Parihar, a researcher with Botanical Survey of India (BSI) has been focusing on macro fungi for more than 15 years. When he and his team were exploring the forests in West Kameng district, they stumbled upon no less than 40 of the thick, leathery fruiting bodies of the new species (Bridgeoporus kanadii) growing on old growth Abies or fir trees.

What makes the genus stand out is its sheer size – the smallest was nine centimetres in radius, and the largest grew wider than three metres. “It is so large that I could sit on it, and it remained firmly attached to the tree,” said Parihar.

A deep-sea squid discovered in tropical waters

In the Arabian Sea well off the coast of Kollam district, Kerala, in March 2024, fishermen spotted a curious bycatch in their nets. The Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI) researchers in Kochi, collected it for a closer look.

They conducted morphological and phylogenetic assessments to prove that it’s a new-to-science species and described it Taningia silasii. The finding was led by study authors Geetha Sasikumar, who primarily studies shellfish, and K.K. Sajikumar who researches cephalopods.

These squids inhabit the twilight and midnight zones (waters deeper than 200 m), down to the sea floor – depths that are difficult to study. “Taningia squids are very fast swimmers and generally don’t inhabit inshore waters, so it’s not easy to find even one, let alone track populations,” said Sasikumar.

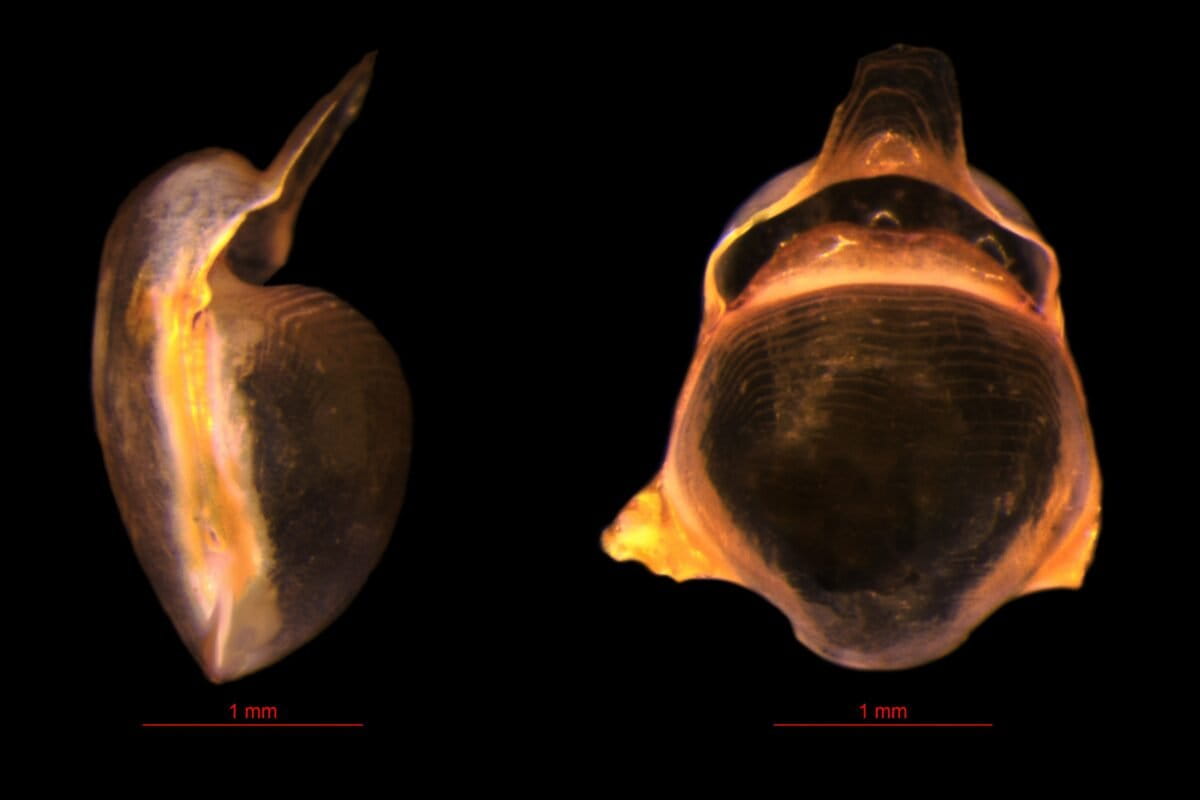

New sea butterflies from old marine samples

In 2019, marine biologist Kiran Shah was sorting through small bottles containing sand and rocks, which had been gathering dust for years in a lab located on a hilltop in Port Blair. These bottles with samples were collected by marine scientists in 2011. In these samples, Shah found four pteropod species new to India.

There are two types of pteropods: sea angels (without shells) and sea butterflies (with shells). Shah’s description of four species of sea butterflies – Diacavolinia pteropods (D. deshayesi, D. grayi, D. mcgowani, and D. strangulata) discovered in Indian waters for the first time.

This discovery increases India’s pteropod species count from 22 to 26 and comes at a critical time when pteropod populations are showing signs of decline globally because of warming oceans. “The availability of pteropods signifies that the region of Andaman and Nicobar Islands has a healthy ecosystem,” said Shah.

A long-wait for the new long-tailed bat

In 2016, bat researcher Rohit Chakravarty first caught this new bat species – the Himalayan long-tailed Myotis (Myotis himalaicus). “Though it did seem different from the other bats I had caught, I didn’t have any suspicions [it was a novel species],” he says.

After completing the fieldwork, while studying its DNA sequence, there was a significant genetic divergence from other similar species within the Myotis frater complex. However, to confirm it as a new species, researchers needed a specimen to study the morphological and anatomical characteristics. It took Chakravarty and his team five years to catch another specimen.

In 2021, when Chakravarty finally caught the bat, he knew immediately that his long search had come to an end. The Himalayan long-tailed Myotis as the name suggests, has a tail almost as long as its body. The specimen was heavier (by 2-3 grams) than other Myotis found in the region, and it had a distinctive bare patch around the eye.

A burrowing snake found in a coffee plantation

In 2015, tourist guide Basil P. Das and his father set out to tend to the plants in their coffee plantation in the village of Jellipara in Palakkad district in Kerala. As they began to till the soil in their farm, a small black and cream-coloured snake that they had never seen before, wriggled loose from the earth.

Das took a photo of the snake and sent it to his friend David V. Raju, a naturalist, who could not recognise the species. The snake specimen was eventually handed over to Vivek Cyriac who runs the Shieldtail Mapping Project (SMP), a citizen science initiative to document shieldtail snakes. A decade later, it turns out that the Das family had found a new species of snake — Rhinophis siruvaniensis.

Local farmers had traditional knowledge of this species’ behaviour and seasonal patterns, even though it had not been scientifically documented until now, according to the study. “When I told my neighbours that I had found this new snake, they told me they had seen it many times before,” said Das.

Compiled by Priyanka Shankar.

Banner image: The lateral and ventral view of Diacavolinia strangulata. Images by Shah et al. The species was recently discovered in the Indian waters for the first time.