A growing number of Americans are betting on game scores, weather patterns, technology releases, and even when singer Taylor Swift and football player Travis Kelce will get married. They are joining prediction markets – online pools wagering on the outcomes of real-world events – that have turned niche speculation into a mainstream form of trading.

These betting markets are booming, with trading up from $9 billion in 2024 to more than $44 billion in 2025. They are valuable, experts say, because they often create more accurate forecasting models in politics and business than traditional polls. And bettors say crowdsourced wagers are a fun – and potentially profitable – way to engage in sports, such as the Olympics, and other events.

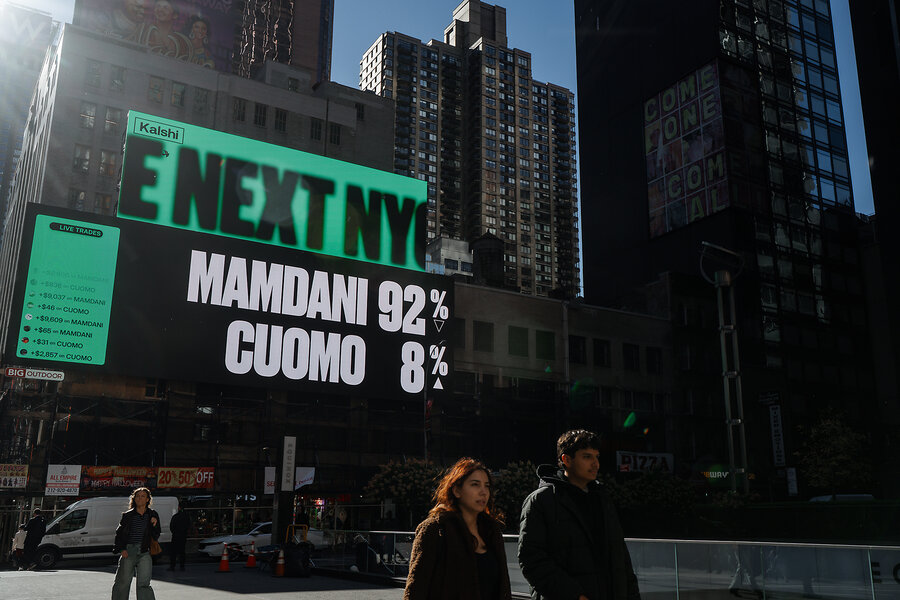

With the boom has come backlash, though, not just from sports fans but also from sports leagues and public officials worried about the risk of rigged wagers where a player might balk for a bet. The NFL, for example, banned ads for prediction market sites including Kalshi, PredictIt, and Polymarket during the Super Bowl, citing concerns about legal gray areas and game integrity.

Why We Wrote This

Prediction markets, where people can bet on outcomes of real-world events, often forecast better than traditional polls. But the evolving markets also raise concerns about cheating and corrosion of trust.

But the risks extend beyond these markets to other forms of wagering – such as recent sportsbook-betting allegations involving NBA figures. One notable historical precedent is the 1919 “Black Sox” scandal, in which several Chicago White Sox players took bribes to throw the World Series, a conspiracy that shattered public trust and led to lifetime bans for stars like Shoeless Joe Jackson.

“For many centuries, people have wanted to legally restrict these sorts of activities,” says Robin Hanson, a George Mason University economist and a pioneer in prediction markets research.

“Yes, we’ve carved out exceptions because we see social value in them,” he says, referring to once-illegal activities such as stocks, insurance, and auctions. “But technically, they’re all gambling.”

How did prediction markets start, and why are they popular?

In the early 1900s, betting markets on elections often exceeded the value of transactions on the U.S. stock exchanges.

As the accuracy of and trust in election polling have faltered, interest in prediction markets has resurfaced.

In traditional legal gambling, people place bets against “the house,” which sets fixed odds and is regulated at the state level. In prediction markets, people are betting directly against each other, and the marketplaces are regulated federally as exchanges. In both cases, the businesses make money through different forms of transaction fees. And in both cases, bettors can win multiples of what they wager, if betting against the odds.

Modern prediction markets trace their origins to 1988, when professors at the University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business developed a market to predict the winner of that year’s presidential race between George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis. (The idea, now known as the Iowa Electronic Markets, was that people who bet their own money on outcomes would produce more accurate predictions than standard polls.)

Today, sites allow people to place bets – or “event contracts” – on real-world events that could happen in the future. These are typically simple “yes” or “no” bets of up to 99 cents with payouts based on how many people participate and the odds of the event happening.

“The long-term vision is to financialize everything and create a tradable asset out of any difference in opinion,” Tarek Mansour, a Kalshi co-founder, said at a conference last year.

Why the pushback?

Critics see prediction markets as increasingly risky and part of a rise in “the gamblification” of society.

Earlier this year, several states moved to restrict prediction market activities, arguing that the companies were using the markets not only for legitimate forecasting but also for sports gambling.

In a Feb. 2 statement, New York Attorney General Letitia James warned that prediction sites could expose New Yorkers to significant financial risk and that the industry could face penalties for unlicensed sports wagering in New York. Online betting in general (not limited to prediction markets) has been linked to an increase in bankruptcies. About 1 in 5 online sports bettors – often young men – show signs of a gambling disorder.

Why are sports leagues and public officials speaking out?

The NFL and other sports leagues now accept standard sports betting, but some are concerned about looser regulations governing the new – albeit similar – prediction markets. Betting, many argue, can attract new fans and keep existing ones engaged. The NHL, for one, has partnered with prediction markets like Kalshi and Polymarket. And there are already active, legal, and regulated prediction markets in play ahead of the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan-Cortina.

But golf’s PGA Tour, like the NFL, has officially blocked players from endorsing prediction markets, saying they operate in a regulatory gray zone that creates legal and reputational risks. And while the NBA has not issued a league-wide ban, it has voiced concerns. Bets, some league officials argue, undermine the integrity of games and the trust that binds teams and fans.

The NCAA is facing a point-shaving scandal – in which players sabotage games to make money – involving dozens of people and multiple teams. In January, the NCAA president called for a pause on the use of prediction markets for college sports.

Beyond sports, public officials worry that prediction markets allow insiders to make “signal bets,” or moves meant to identify undervalued betting opportunities, giving one group of bettors an advantage over the general public. Critics also say that betting on violent or lethal events could cross moral and ethical boundaries.

Last June, one Polymarket “yes/no” bet was on “Israel military action against Iran by Friday.” When the strike happened, one user made $128,000 on the bet. Another user profited more than $400,000 on a contract over when Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro’s rule would end, raising concerns of inside knowledge of the U.S. raid that ousted him.

U.S. Rep. Ritchie Torres, a New York Democrat, recently introduced the Public Integrity in Financial Prediction Markets Act of 2026, which, if passed, would bar government officials from using insider information for financial gain.