- The Aravalli mountain range acts as a natural barrier against dust from the Thar desert on the west, but mining and human encroachments are steadily degrading this protection.

- The lack of a strict land use policy facilitates the reduction of green areas like the Aravallis which can mitigate dust and pollution, experts note.

- The increase in air-soil interaction caused by deforestation or loss of green cover helps disease-causing microbes to persist and spread along with the dust.

India’s capital region is witnessing another smoggy winter with severe air pollution. As the Delhi government deploys various dust control measures in the capital, the hills of a shrinking Aravalli range — which guard India’s mainland from the dust of the Thar desert in the west — are caught up in a legal battle for protection.

North India experiences five to ten dust storms annually between March and June, killing people, damaging property and worsening the already compromised air quality in the region. A recent study also found a positive correlation between rising temperature and increasing aerosol load in India’s atmosphere. “As per our analysis of satellite data from 2019 to 2023, the major aerosol hotspots in India are the regions of Ladakh, Western Ghats, Thar desert, Rann of Kutch, parts of Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, and Punjab,” the corresponding author of the study Sangem Giriraj, told Mongabay-India.

Experts point out that the degradation and mining of the Aravalli range is weakening a key natural barrier against desert dust, potentially worsening air pollution across northern India.

Mining and dust

“Obstacle dunes found on the western or Thar desert side of the Aravalli hills are the most compelling evidence that the Aravallis block desert sand,” says Chetan Agarwal, an independent forest and environmental services analyst, based on his analysis of Google Earth images. These dunes have formed over hundreds of thousands of years as the Aravalli hills slowed down the western desert winds causing deposition of the heavier sand particles, adds Agarwal.

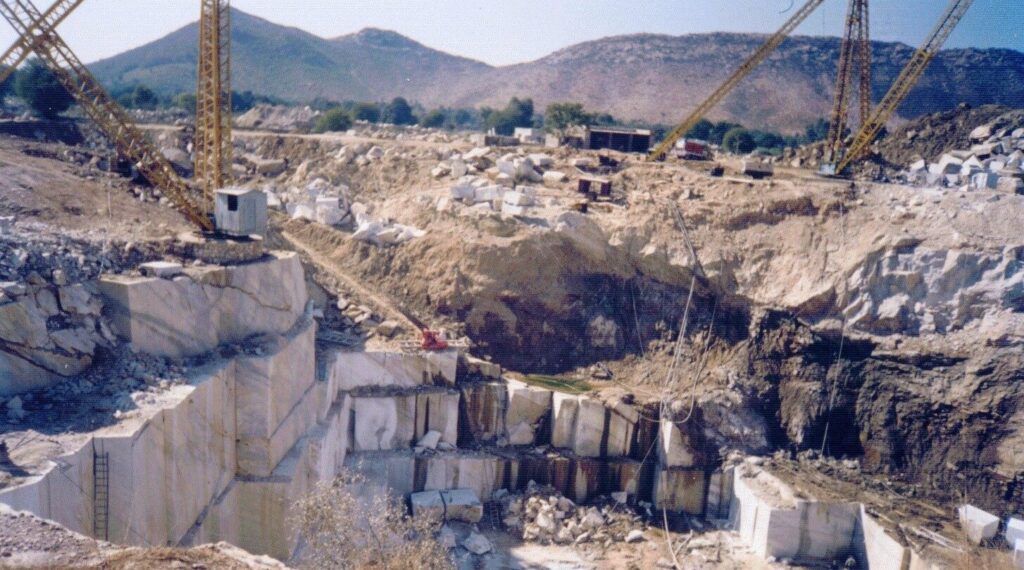

However, mining for minerals, in parts of the Aravalli hills, is leading to degradation of this geological barrier. According to a report by the People for Aravallis collective, more than a dozen breaches have been noted in the Aravallis between Ajmer and Haryana.

“The decisions are mostly made on the financial cost-benefit analysis, not considering the environmental or societal welfare. For example, the increase in land value of converting an urban forest to real estate is fifty to a hundred times. Every government thinks that the Aravallis are so big; what is the harm in allowing mining or real estate in a few thousand hectares? But, cumulatively, all of these have an impact,” states Agarwal.

There is also evidence that dust from mining could suffocate nearby forests. It is linked to a range of respiratory diseases such as silicosis and asbestosis in mine workers and local residents.

“We need controlled mining with quantitative quotas, and that also in areas with minimal impact on forest, wildlife, ecology and local people. As a society, we also need to reduce consumption and work towards finding alternate construction materials,” says Agarwal.

Though there are ongoing efforts to restore these forests, it is not always feasible. “Mining in Aravalli often goes hundreds of metres deep, destroying the soil, leaving the land unsuitable for restoration through plantation,” says Vikrant Tongad, founder of the Noida-based organisation SAFE (Social Action for Forest and Environment). “This [mining] is another way of destroying this dust barrier, as without trees, a barren Aravalli is unable to trap the dust load alone.”

Increasing pathogens

Air pollution is a public health hazard that caused over eight million deaths globally in 2021. Inhaling polluted air affects lungs and other organ systems, causing severe diseases. Additionally, studies have found that fog increases atmospheric microbial load by more than 30% over the central Indian Gangetic Plain (IGP) by stalling wind movement, therefore allowing safe gathering of local pathogenic microbes besides the ones travelling from the western IGP.

“Temperature and seasonal wind also influence the diversity of regional pathogens. Thus, we have found that continental dry winds coming from western India and the IGP during the pre-monsoon season introduce 15% unique microbes in the Darjeeling hilltop in the eastern Himalayas,” says Sanat Kumar Das, an associate professor at Bose Institute, Kolkata, whose lab conducted the study.

When Das and his team studied the winter air of populous Delhi, they found that compared to normal winter days, air samples of hazy days from highly populated areas had 50% more microbial diversity, while less populated areas revealed 25% diversity only. “We are nothing but small and big pumps discharging pathogens by sneezing, coughing or shedding from our skin,” Das comments.

Dust also travels to India from the distant Arabian Desert, and the north-African eastern coast and gets reinforced with the dust arising from the Thar desert before reaching inland. During long-distance journeys, dust particles give airborne microbes a safe ride. “Besides protecting them from fatal ultraviolet radiations, dust particles provide necessary nutrients for the microbes to survive during long journeys,” says Das.

He adds, “Be it in deserts or cities, the more the air-soil interaction, caused by lack of greenery and deforestation, the more nutrients that reach the airborne microbes through dust, helping these pathogens to thrive and escalate disease outbreaks.”

Land use policies for clean air

Urban sprawl and the change in land use in the high-density rural areas are reducing vegetative cover in India. Between 1975 and 2019, almost 8% of the forest has disappeared in the Aravallis, according to a 2022 study.

Ghazala Shahabuddin, visiting faculty of Environmental Studies at Ashoka University, who works on the ecological impacts of land use change, forest exploitation and habitat fragmentation, says that the lack of a legal framework for urban and suburban greening allows such rampant urban expansion and unsustainable mining practices in the low Aravalli hills that border megacities such as Gurugram, Alwar, Udaipur, Delhi and Faridabad. “There are actually no specific land use policies in Indian cities, which results in continuous change and transformation of urban green areas including city forests and fallows in suburban spaces,” she says.

“This is unfortunate that when we are suffering so much due to air pollution and global warming, there is still no legal requirement for city municipalities to keep a particular percentage of the city area under green cover. Neither are there strict guidelines for maintaining multi-layered, diverse native vegetation that is more effective in trapping dust and other pollutants than exotic plants and tree monocultures that are commonly used for ‘greening’.”

Tongad agrees with Shahabuddin and adds, “In the revenue records, most green areas and water bodies in the country are not even officially recorded. However, when an area is legally notified as a green zone — such as in a city master plan or at the district level in revenue records — changing its land use becomes very difficult. This makes it harder to divert these green areas for non-environmental purposes, which is beneficial from an environmental perspective.”

Although in Delhi and its surrounding regions several builders have attempted — both legally and illegally — to change the land use of green areas marked in master plans for their own benefit, and some have even succeeded, environmental conservationists have successfully opposed at least ten such cases where private developers tried to occupy designated green areas simply because they were located in prime locations, Tongad shares.

“With the launch of the Green Wall Plantation Project by the Union Ministry of Environment, plantation activities in degraded parts of the Aravalli are expected to become more feasible. SAFE is currently working towards securing a contiguous land parcel, along with the required land-related NOCs (No Objection Certificates) and resources, to undertake large-scale plantation work,” he adds.

“We need to call an embargo on further construction in certain cases, as most of the ongoing construction could be for real estate speculation, not for people to live in. Probably real estate is driving the economy of our country right now, and unfortunately some of the mining in Aravalli is stone and marble quarrying for urban construction while destroying the local habitations and agrarian livelihoods, as has been documented by the People for Aravallis collective,” remarks Shahabuddin. Land use planning and its strict implementation is necessary, she says. “Otherwise the same process of land use change will affect one mountain chain after another.”

Read more: With a new identity, the Aravalli hills stare at an uncertain future

Banner image: A marble mine in the Aravallis located adjacent to Sariska Tiger Reserve in Alwar district, Rajasthan. Image by Ghazala Shahabuddin.