Getty Images

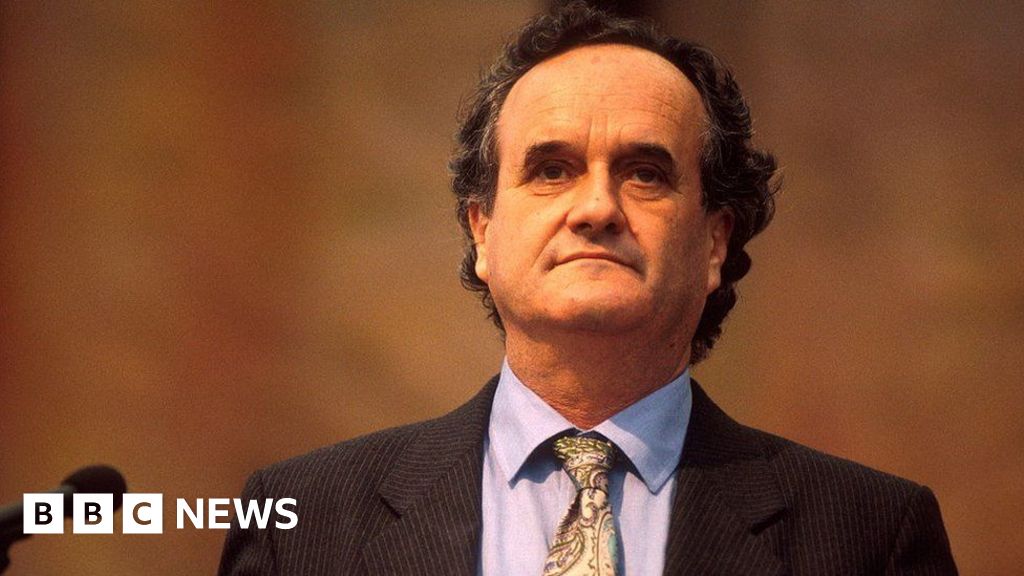

Getty ImagesThe broadcaster and journalist Sir Mark Tully – for many years known as the BBC’s “voice of India” – has died at the age of 90.

For decades, the rich, warm tones of Sir Mark were familiar to BBC audiences in Britain and around the world – a much-admired foreign correspondent and respected reporter and commentator on India. He covered war, famine, riots and assassinations, the Bhopal gas tragedy and the Indian army’s storming of the Sikh Golden Temple.

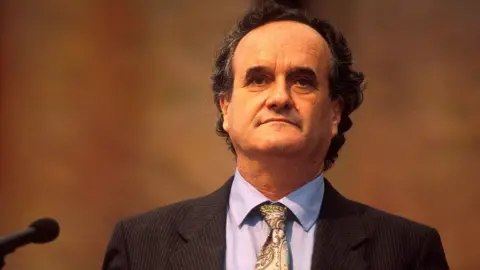

In the small north Indian city of Ayodhya in 1992, he faced a moment of real peril. He witnessed a huge crowd of Hindu hardliners tear down an ancient mosque. Some of the mob – suspicious of the BBC – threatened him, chanting “Death to Mark Tully”. He was locked in a room for several hours before a local official and a Hindu priest came to his aid.

The demolition provoked the worst religious violence in India for many decades – it was, he said years later, the “gravest setback” to secularism since the country’s independence from Britain in 1947.

“We are sad to hear the passing of Sir Mark Tully,” Jonathan Munro, Interim CEO of BBC News and Current Affairs, said in a statement. “As one of the pioneers of foreign correspondents, Sir Mark opened India to the world through his reporting, bringing the vibrancy and diversity of the country to audiences in the UK and around the world.

“His public service commitments and dedication to journalism saw him work as a bureau chief in Delhi, and report for outlets across the BBC. Widely respected in both India and the UK, he was a joy to speak with and will be greatly missed.”

India was where Sir Mark was born – in what was then Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1935. He was a child of the British Raj. His father was a businessman. His mother had been born in Bengal – her family had worked in India as traders and administrators for generations.

He was brought up with an English nanny who once chided him for learning to count by copying the family’s driver: “that’s the servants’ language, not yours”, he was told. He eventually became fluent in Hindi, a rare achievement in Delhi’s foreign press corps and one which endeared him to many Indians for whom he was always “Tully sahib”. His good cheer and evident affection for India won him the friendship and trust of many of the top rank of the country’s politicians, editors and social activists.

Throughout his life, he performed a balancing act: English, without doubt; but not – he insisted – an expat who was passing through India. He had roots there; it was his home. It’s where he lived for three-quarters of his life.

Immediately after World War Two, at the age of nine, Sir Mark came to Britain for his education. He studied history and theology at Cambridge and then headed to theological college with the aim of being ordained as a clergyman before he – and the church – had second thoughts.

He was sent to India for the BBC in 1965 – at first as an administrative assistant, but in time he began to take on a reporting role. His broadcasting style was idiosyncratic, but his strength of character and his insight into India shone through.

Some critics said he was too indulgent of India’s poverty and caste-based inequality; others admired his clearly expressed commitment to the religious tolerance upon which independent India was anchored. It’s “really important to treasure the secular culture of this country, allowing every religion to flourish,” he told an Indian newspaper in 2016. “… we must not endanger this by insisting on Hindu majoritarianism”.

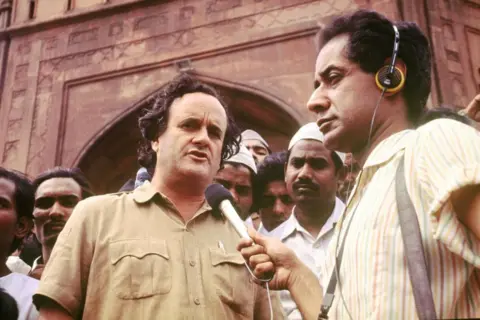

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSir Mark was never an armchair correspondent. He travelled relentlessly across India and neighbouring countries, by train when he could. He gave voice to the hopes and fears, trials and tribulations, of ordinary Indians as well as the country’s elite. He was as comfortable wearing an Indian kurta as in a shirt and tie.

He was expelled from India at 24 hours’ notice in 1975 after the then prime minister, Indira Gandhi, ordered a state of emergency. But he headed back 18 months later and had been based in Delhi ever since. He spent more than 20 years as the BBC’s head of bureau in Delhi, leading the reporting not simply of India but of South Asia, including the birth of Bangladesh, periods of military rule in Pakistan, the Tamil Tigers’ rebellion in Sri Lanka and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Over time, he became increasingly out of step with the BBC’s corporate priorities, and in 1993 he made a much-publicised speech accusing the then director general, John Birt, of running the corporation by “fear”. It marked a parting of the ways. Sir Mark resigned from the BBC the following year. But he continued to broadcast on BBC airwaves notably as presenter of Radio 4’s Something Understood, turning back to issues of faith and spirituality which had engaged him as a student.

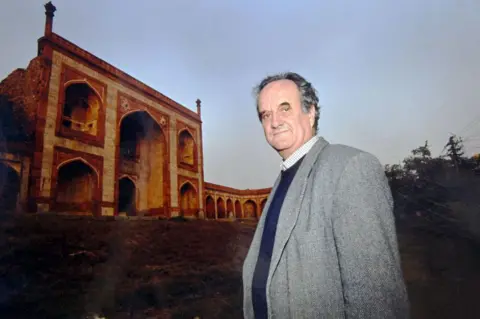

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUnusually for a foreign national, Sir Mark was accorded two of India’s top civilian honours: the Padma Shri and the Padma Bhushan. Britain too gave him recognition. He was knighted for services to broadcasting and journalism in the 2002 New Year’s honours list. He described the award as “an honour to India”.

He continued to write books about India – essays, analyses, short stories too, sometimes in collaboration with his partner, Gillian Wright. He lived un-ostentatiously in south Delhi.

Sir Mark never gave up his British nationality but was proud also to become late in life an Overseas Citizen of India. That made him, he said, “a citizen of the two countries I feel I belong to, India and Britain”.