The incidents made visible the growing schism between Skeet Jones and his nephew, Brandon Jones, the county constable. Skeet’s faction maintains that they have been the subjects of political persecution. Brandon—who is widely suspected of being the livestock investigator’s confidential informant—has argued that his uncle runs the town as though he’s above the law. (Brandon declined to comment on the identity of the informant.) Both sides have filed a flurry of lawsuits and countersuits naming each other. (The filings, with their absurdly heightened rhetoric, can make for odd reading. In an application for a temporary restraining order and injunction against Brandon, one of Skeet’s allies claimed, among other things, that Brandon raised his eyebrows “in an intimidating manner” during a proceeding.)

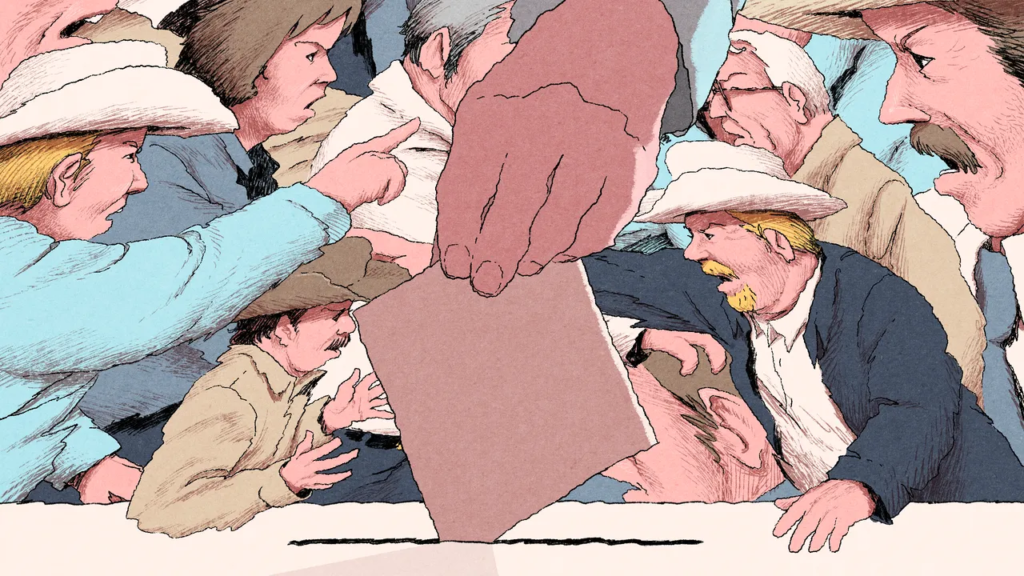

Elections have become proxy battles in the family war, with each side furnishing candidates for local offices. (Loving County is, on the whole, a deeply conservative place, but a number of its elected officials—including Skeet—run as Democrats, as if the political realignments of the past seventy years had bypassed the county while its residents were consumed by more local concerns.) “Any voter can challenge the registration of any other voter, and, in Loving County, just about every vote we have has some kind of civil challenge,” David Landersman, the county sheriff, said. He also serves as the county’s voter registrar.

The feud in Loving County is marked by both intensity and stasis, with the two sides locked in a small-town version of trench warfare. One recent election was won by a single vote; another resulted in a tie. Then, in 2024, a third element entered the system, in the unlikely form of a hustle-culture evangelist from Indiana named Malcolm Tanner.

In 2023, Teresa, a woman living in South Carolina, was driving a snaking road down a mountain when a word popped into her head: “Texas.” Two years later, it happened again. This time, the word was “West.” Shortly afterward, she saw a social-media post by Tanner, a tall and confident self-proclaimed C.E.O. and real-estate mogul. Tanner spoke in a blend of political rabble-rousing and entrepreneurial uplift. He urged his three hundred thousand Facebook followers to head to a place that Teresa was hearing about for the first time: Loving County. “See you in Texas soon,” he wrote in a post. “Thank you all for saying YES to finding a true political home with us!”

Owing to its wealth, the county had caught the attention of political interlopers in the past. In 2005, a handful of libertarians attempted, with little success, to wrest control of the government. The idea of taking over the county occasionally circulates on X and YouTube as “the craziest deal in America.”

Tanner had pitched a number of grand visions in recent years. He was going to develop a dilapidated former Y.M.C.A. building in central Indiana into a hotel; he was going to host a Million Man March, also in Indiana; he was going to run for President and institute reparations for what he referred to as “melanated people.” None of his schemes panned out. Then, in 2024, he turned his attention to Loving County. Tanner’s followers could move to Texas, win elected positions, and receive “free political homes,” he claimed. (He also suggested a new name: Tanner County.) On Clubhouse, the live voice-chat platform, he hosted raucous, engaging meetings twice a day. “I retired, I was bored, and it was just something to do. I was meeting a lot of people, you know, melanated people from all over the world—good people,” Erica Marshall, a former member of Tanner’s circle who has become one of his most vocal critics, told me. Tanner was “very manipulative,” she said. “He’s managed to have people quit their jobs, leave their homes. They sold all of their things except the stuff that they could fit in their car, and they went to Loving County, just like that.” (Marshall never made it to Texas.)

In October, I drove to Mentone. It was my first time in Loving County and, given all I’d heard about the sparse population, I was expecting tumbleweeds and eerie Panhandle silence. But the town was bustling, the roads full of pickup trucks and heavy equipment; at the gas station, I had to wait in line for a pump, as oil workers commuted to and from work.