But many Minnesotans might also no longer be sure if protests today will lead to change. If this is the case, their hesitancy is likely shared by many of their fellow-Americans who, in the past year, have dutifully shown up to large-scale marches around the country, such as “No Kings” day, but who do not appear to expect anything more from these mass gatherings than an opportunity to vent and to feel camaraderie and kinship.

The truth is that, thanks to the two-party system, relative economic comfort, and basic stability, many of us in America do not have much in the way of political imagination. Nostalgia certainly plays a role in our limited view—we are always re-creating the marches we learned about in history class—but it’s increasingly clear that the internet and social media also have a diluting effect on dissent, creating the illusion of strength through volume while somehow watering down everything in the process. We can tweet, go protest, and vote. That’s about it.

During the past fifteen or so years, we have seen a handful of revolutions-that-weren’t, from the Arab Spring to the summer of George Floyd to the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong. Today, we are watching yet another insurrectionary moment in the streets of Iran. The ceding of nearly all communication to the internet might be generating a pattern of online flareups followed by enormous, stirring street protests. What remains unclear, as chronicled by Vincent Bevins in his excellent book “If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution,” is what happens after the streets empty and people go back to their phones. Bevins, who published the book in 2023, argued that what we have seen so far, at least, is that the protests fail to achieve much in terms of material or political goals and are followed by periods of intense backlash and repression.

Before Good was killed in Minneapolis, I was already thinking about Bevins’s book, as the sabres rattled after the capture of the Venezuelan President, Nicolás Maduro. The Trump Administration, through some cockeyed revision of the Monroe Doctrine, seems eager to stake a claim to the entire Western Hemisphere. After Maduro’s capture, the Trump War Room account on X posted a cartoon of the President straddling North and South America with a big stick reading “Donroe Doctrine” in his hand. A litany of possible military targets emerged throughout the week, communicated via leaks, press conferences, and statements from the Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, and from Donald Trump himself. Greenland, Colombia, and Cuba have all been named as places that should be on high alert for some measure of American military expedition. (Mexico’s President, Claudia Sheinbaum, said this week that, after speaking with Trump, the U.S. would not be invading her country.) A year ago, the invasion of Greenland felt like a joke, or, at worst, a sign of Trump’s deteriorating grip on reality. Today, it seems inevitable that America will seize Greenland from Denmark and will then turn its eye back to Central and South America. Congress appears utterly incapable of restraining the Administration’s adventurism, and condemnation from foreign leaders seems only to add new names to the list of America’s enemies.

The public, according to polls, does not support the President’s expansionism. Only a third of respondents in a recent poll approved of the operation to capture Maduro; around nine in ten said that the Venezuelan people, not the United States, should control who governs them. On a broader level, Trump and Rubio’s imperialist aims cut against the priorities of the vast majority of their constituents: only twenty-seven per cent of respondents polled in September wanted the U.S. to take a “more active role” to “solve the world’s problems.” Readers of this column know that I’m skeptical of opinion polling—except when results are more or less uniform and conform to a coherent picture of the electorate. In this case, a country that endured seemingly unending wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and that has watched the wars in Ukraine and Gaza extract incalculable humanitarian and financial tolls might be wary of military interventionism.

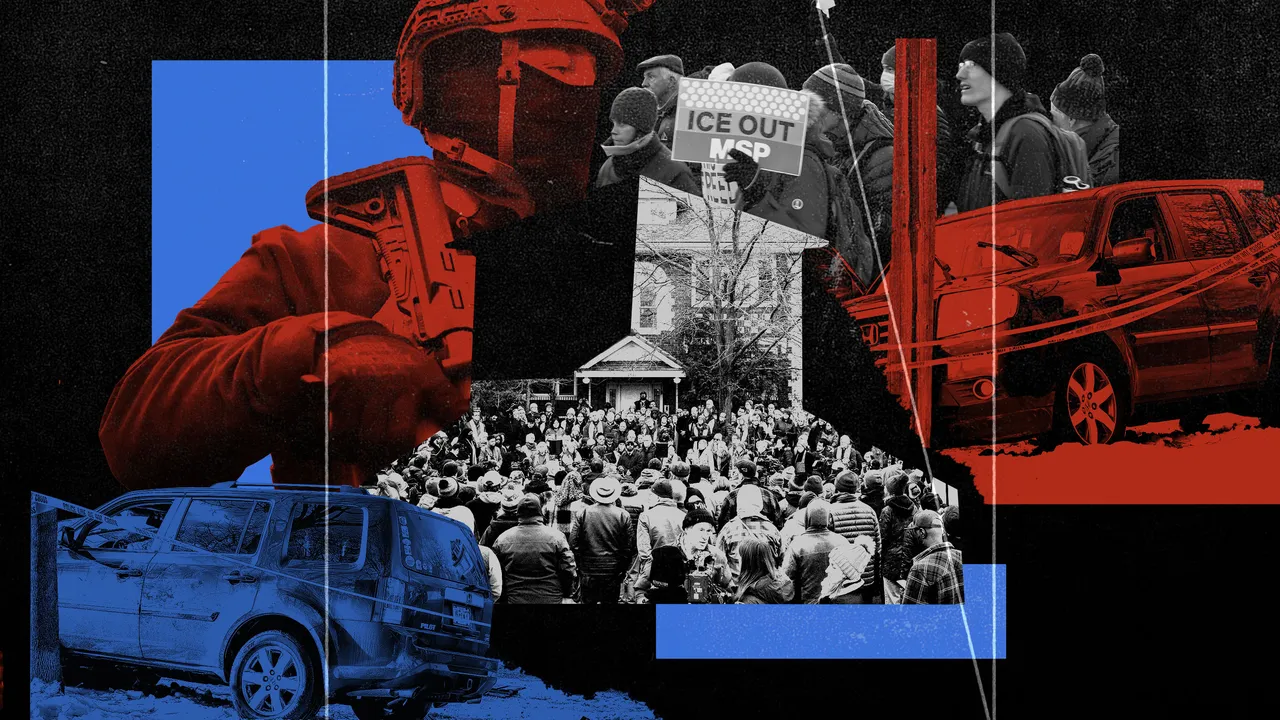

ICE is not popular, either. A few hours before Good was killed, YouGov released a poll showing that only thirty-nine per cent of Americans approved of how the agency was doing its job. Regardless of what you think about the laws concerning justifiable force—which, in any case, have been muddied by ICE’s wanton disregard for due process and for normal law-enforcement procedures—there was no reason for an agent to fire multiple times into a car that was travelling at a modest speed and seemed to be trying to move out of the agents’ way. The attempt by Kristi Noem, the head of the Department of Homeland Security, to smear Good as a “domestic terrorist” has only fuelled public indignation. Lies will not convince Americans who watched an ordinary person get executed by a panicked federal agent in a mask. Even those who believe that Good should not have been impeding law enforcement are unlikely to support what Noem seemed to be doing, which was celebrating the death of a supposed terrorist.