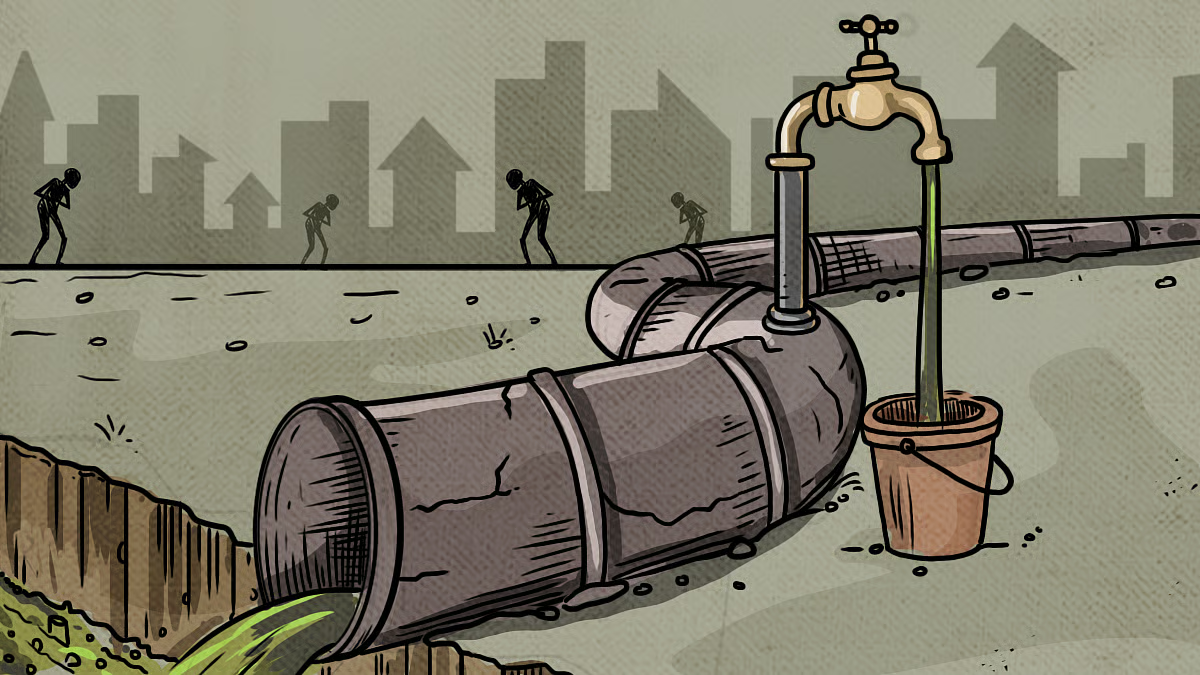

When people die in India’s cleanest ranked city, Indore, because of dirty drinking water, shock and condemnation are justified. But this is not really about Indore, nor is it about water supply. It is about sewage—the excreta that we flush and forget every day. The problem is, we do not join the dots. Every city administration and successive government focus on water supply but ignore the fact that for every litre supplied, 80 per cent returns as wastewater. In our current system, this return flow or sewage is so expensive to intercept or treat that it is largely ignored until it resurfaces, mixed in our drinking water or polluting our lakes and rivers. So, unless we start obsessing about wastewater, clean-water security will remain elusive. This is the lesson from Indore.

India’s programmes for urban areas recognise this imperative, but not enough is happening to change the design of water and sewage provisioning. The Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) finances water supply, sewage and green infrastructure. As per the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Rs 1,93,104 crore has been spent on some 3,500 projects over the past decade. But water supply tops the priority with 62 per cent of spending, compared with 34 per cent on sewerage. Rejuvenating waterbodies, which would allow groundwater recharge and augment water supply, has taken up a minuscule 3 per cent.

This needs to change—not by spending more on sewerage, but by redesigning infrastructure so it is affordable. Only then will cities have the resources to ensure that every drop of wastewater is intercepted, treated and reused. Today’s water-supply model relies on pipes and pumps that transport water from long distances as local sources either dry up or get polluted. Indore, for instance, once depended on local reservoirs and lakes; it now proudly draws drinking water from the Narmada, 70 km away. This is, when we know that the longer the water pipeline, the more expensive it is to build; they also leak more and consume more electricity for pumping. All this adds to the price of water supplied, mounting to the point where even the rich cannot afford the capital and operational cost of basic water and there is never enough money to subsidise all. As a result, even in Narmada-connected Indore, households rely on groundwater for drinking. When sewage is not properly intercepted, this becomes a public-health disaster waiting to happen.

Today, sewerage plans revolve around ever more pipes and pumps that never get completed. In each case, households need to be connected; sewage drains need to be retrofitted; and roads need to be dug up endlessly.

This wastewater is then pumped through underground networks to treatment plants and discharged into drains, rivers or lakes, already choked with untreated sewage of the majority who remain unconnected. The effort is largely “wasted”. But the cost is mindboggling. Invariably, these projects face delays and cost-overruns. By the time, one sewage network is completed, another part of the city has imploded and needs to be connected. This is also why much of India remains unsewered and most households depend on toilets connected to onsite systems—some kind of septic tank or tank. In Indore, leakage from such onsite toilet systems contaminated drinking water.

These onsite systems need not be the problem. They are, in fact, the solution for the future. But they will work only if it is ensured that toilets are desludged, the excreta are taken for treatment and the treated water (not wastewater) and solid are reused as manure or fuel. Without this, the water supply will always be at risk of contamination. So, sewage management must come first before water supply.

We also need to place affordability of sewage management at the centre. AMRUT guidelines must be redesigned to prioritise sewage management, including total interception of excreta from households. To make it affordable, cities should be incentivised to use existing network of on-site septage tanks. Ensure that tankers, not undergound pipes, take this septage to treatment facilities. This is faster, cheaper and more inclusive. Second, guidelines must incentivise reuse; cities should be paid so that they send the treated wastewater for reuse and the sludge for bio-enrichment or fuel. In this way, the project would be designed, not for sewage interception or for building standalone sewage treatment plants, but for wastewater reuse. Financing should be linked to the volume of wastewater and sludge recycled.

Third, water projects must be connected to local sources, including the rejuvenation of waterbodies. This will reduce costs of long-distance transfers, make groundwater more sustainable and water supply more affordable. But this is only possible with the sewage-first approach. As long as waterbodies continue to be polluted, cities will continue their search for cleaner water from increasingly distant places. In this way the cycle of clean water to deadly water will persist. This should be the learning from the Indore tragedy.