President Donald Trump’s declaration on social media of a “total and complete” blockade of sanctioned oil tankers entering or leaving Venezuela is a striking military move that ramps up U.S. pressure on the country’s leader, Nicolás Maduro.

On its face, the president’s Dec. 16 announcement was textbook gunboat diplomacy. “Venezuela is completely surrounded by the largest Armada ever assembled in the History of South America,” Mr. Trump wrote. “It will only get bigger, and the shock to them will be like nothing they have ever seen before.”

Some analysts warn that if the shock is as considerable as Mr. Trump promises, it could push the food-insecure state toward famine and spark another wave of migration out of the country. Oil is crucial to the Venezuelan economy, accounting for roughly 90% of its exports and more than half its government revenue.

Why We Wrote This

Efforts to stop black market oil tankers from entering or leaving Venezuela signal that U.S. goals go beyond the narcotics trade to include pressure on the Maduro regime.

Precisely because blockades deny countries access to goods and commerce, potentially leading to dire consequences, they are considered acts of war.

Mr. Trump’s latest show of force isn’t technically a blockade, but the administration appears eager to show that it is ready for battle. It has deployed bombers and warships, including the world’s largest and most advanced aircraft carrier, to the Caribbean.

On Dec. 10, the United States tracked and got a federal warrant to seize the Skipper, a sanctioned tanker transporting Venezuelan and Iranian oil. Mr. Trump says he plans for the U.S. to keep the ship’s cargo.

On Saturday, the U.S. Coast Guard, under the auspices of the Department of Homeland Security and with the help of the Department of Defense, seized a second tanker, which had recently been docked off the Venezuelan coast. By Sunday, the U.S. was in pursuit of a third tanker that U.S. officials said was operating under a false flag.

These latest moves are reinforcing the sense that the president’s stepped-up military action in the Caribbean is directed not only at narco trafficking, as the administration has previously stressed, but also at forcing Mr. Maduro to relinquish power. The two goals are linked for Mr. Trump, analysts say, as administration officials are calling Mr. Maduro a drug lord and declaring his regime a foreign terrorist organization.

What happens should Mr. Trump’s pressure campaign oust Mr. Maduro gives rise to still more unknowns, analysts say, including whether the U.S. can foster the rise of an opposition-controlled government. In the meantime, the administration’s anti-narcotics campaign carries on: The U.S. military struck two more boats suspected of carrying drugs last week, bringing to 104 the death toll of the campaign, which began in September.

“The idea is to use all levers available” including cracking down on narcotics trafficking as well as black-market oil, “to apply pressure in more and more areas in an effort to convince Maduro to leave,” says Bryan Clark, senior fellow at the Hudson Institute think tank and a retired Navy officer who served as special assistant to the chief of naval operations.

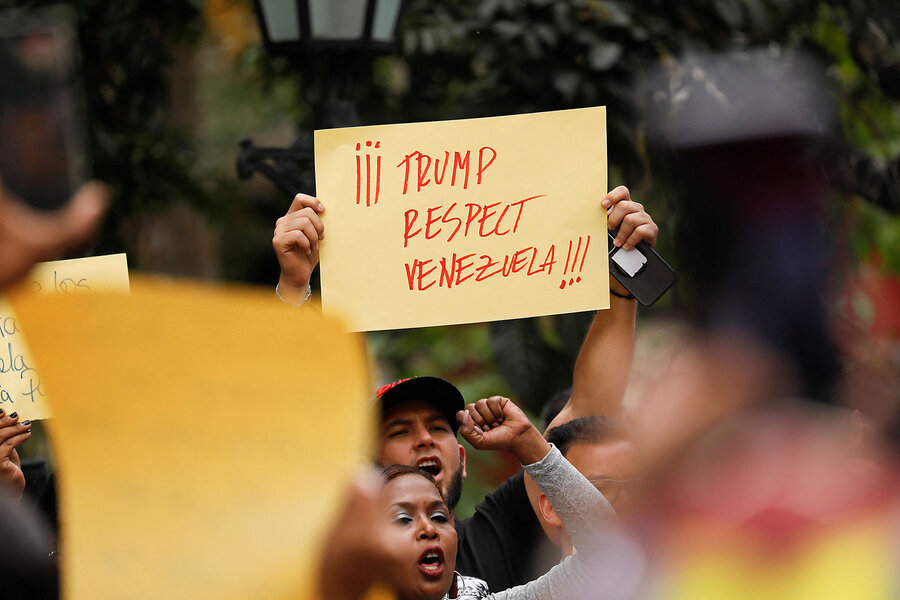

Mr. Maduro denounced what he called the “warmongering threats” of the U.S. He also ordered his navy to begin escorting oil-carrying ships – more a demonstrative move because these are legal vessels not covered under the Trump administration’s latest decree.

Still, analysts say, it raises the risk of escalation in the Caribbean and increases the possibility that the U.S. military could get further involved, too, prompting questions about whether Venezuela and the U.S. are headed for war.

Blockade or quarantine?

The last widely recognized U.S. blockade was during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, to keep the Soviet Union from delivering nuclear missiles to the island.

Though it functioned then as a blockade in practice, the U.S. shunned the term, using “quarantine” instead to avoid the legal implications of an act of war. Today, Mr. Trump is embracing it.

“Blockade sounds more forceful and warrior-like,” says Mr. Clark, who also led development of strategy for the Navy commander’s internal think tank. “But in reality, it’s going to be more like a quarantine, because they’re selectively targeting specific tankers that have been implicated in illegal trafficking in oil.”

The blockade as it is defined by Mr. Trump appears to apply only to oil tankers that are part of an international “dark fleet” of vessels that are already under U.S. sanction.

The question now is what share of Venezuela’s oil trade will be stopped, says Mr. Clark. “Do they go selectively after tankers that have been pre-identified as being bad actors – which means you’re only going after a few tankers and it’s very targeted – or do they end up having some kind of broader inspection regime?”

The second tanker seized was not under sanction, which suggests the administration is trying to cast a wider net.

There are also questions about whether the U.S. military, under Pentagon control, or the Coast Guard, under the auspices of the Department of Homeland Security, will do the halting and inspecting (which could result in more tankers being snared in the U.S. net).

What is clear is that the ability to track vessels is improving. The location of the Skipper, the tanker seized on Dec. 10, was identified using satellites and special technologies “despite its operator’s attempts to falsify its position,” an analysis by Clayton Seigle, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, points out.

The sanctions could affect China and Russia as well. Introducing tanker seizures into Washington’s toolkit, Mr. Seigle said, “will certainly raise eyebrows in China, whose imports of oil from sanctioned suppliers, Russia, Iran, and Venezuela constitute more than a quarter of its import supply chain.”

Military confrontation might not be inevitable

The same holds true for Russia’s shadow fleet, which could have positive effects, from a Ukrainian perspective, on Moscow’s war in the embattled country.

That’s because Russia “relies on a sprawling shadow fleet” of aging tankers with opaque ownership structures to keep its oil flowing despite Western sanctions, Agnia Grigas, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, wrote in a Dec. 17 analysis.

The Trump administration’s latest seizure moves show “that Washington is increasingly willing to treat sanctions evasion not just as a financial violation, but as a maritime security problem,” Dr. Grigas said. This has the potential to negatively affect Russia’s war efforts in Ukraine.

It could also create a deterrent effect, she added, by “demonstrating that shadow fleets are visible, traceable, and vulnerable.”

In Venezuela, though U.S. tanker seizures could hit the economy hard, the pressing question, from the Trump administration’s perspective, appears to be whether it is enough to topple the current regime – whether Maduro leaves on his own or not. And, failing that, whether U.S. boots on the ground will be next.

Most analysts consider a U.S. ground invasion unlikely. Meanwhile, if halting the flow of oil tankers makes conditions on the ground so painful that Mr. Maduro leaves in exchange for an end to the embargo, that wouldn’t necessarily mean success for the Venezuelan opposition, some analysts say.

Should Mr. Maduro’s tenacious hold on power be broken, “the regime as such would try as hard as they can to persist,” says Kurt Weyland, a political scientist at the University of Texas.

Many of those who have worked closely with Mr. Maduro are corrupt and have participated in human rights violations, he adds. “None of them can dare lose power because of the threat of international prosecution.”

That said, despite the U.S. buildup in the Caribbean, there is a sense, too, among some analysts that it could just as easily wind down without a large military confrontation.

“My prediction is that this will eventually go away,” Dr. Weyland says. “The U.S. is not interested in a big military conflict.”

Whitney Eulich in Mexico City contributed reporting for this article.