One of the last messages I sent to the great Iranian stage and screen writer-director Bahram Beyzaie was a recent photograph, taken by a friend, of the interior ruins of Tehran’s oldest cinema, Cinema Iran. There, on one of the walls, hung posters of Beyzaie’s 1988 film Maybe Some Other Time, positioned above and below the torn portraits of the supreme leaders of the theocratic regime.

The symbolism – the ideological ruin; cinema and the future – was too striking for something so accidental, particularly given that Beyzaie’s theatre and cinema are intricate mazes of carefully constructed and overlapping allegorical moments.

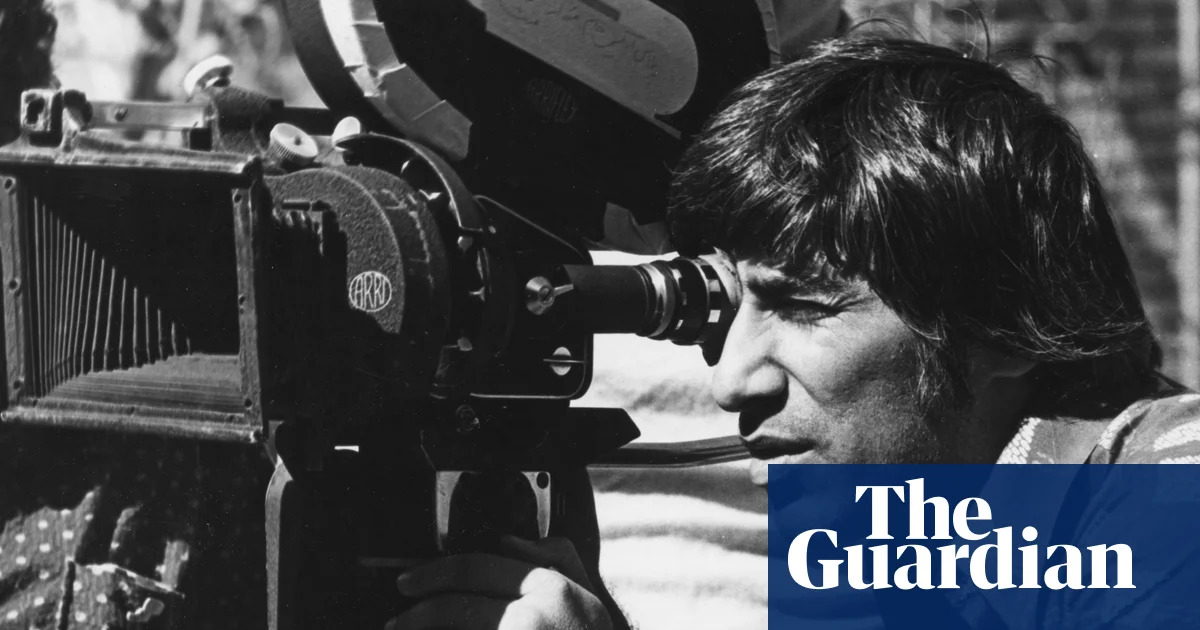

The films of Beyzaie, who died on 26 December aged 87, are seamless blends of myth, symbolism, folklore, and classical Persian literature. Within their dizzying labyrinth of rituals, cinema becomes an act of dreaming.

Outside the cinema, his profound devotion to Iran’s performing arts and literary traditions – both pre- and post-Islamic – resulted in the publication of more than 70 books, including histories, plays and screenplays.

Beyzaie was born on 26 December 1938, into a Bahá’í family in Tehran. His belonging to a frequently persecuted religious minority became, particularly after the 1979 revolution, one of the factors contributing to the censorship of his work.

He began writing plays and film criticism at a very young age, and his now canonical book Theatre in Iran was published when he was only 27.

Like his contemporary Abbas Kiarostami, Beyzaie entered cinema by making short films for Kanoon, the state institution dedicated to producing cultural works for and about children and young adults. His second film for Kanoon, The Journey (1972), which follows an orphaned boy’s search for his parents as it leads him through the polluted wastelands on the outskirts of Tehran, was Beyzaie’s personal favourite. Overflowing with abandoned objects, the film reveals a country discarding its history at a frantic pace.

Beyzaie’s preoccupation with the world of children continued in his finest post-revolutionary film, Bashu, the Little Stranger (1986). In it, an Arab-Iranian boy displaced by war from the south struggles to adapt to life in northern Iran. Beyzaie masterfully links the fragmentation of national identity to language and the failures of communication.

His first feature, Downpour (1972), directed through an energetic and unusual combination of neorealism and political symbolism, was made on a shoestring budget. It tells the story of a young teacher sent to a school in an impoverished neighbourhood, where he falls in love with his student’s elder sister. A jury at the Tehran international film festival, presided over by Satyajit Ray, awarded the film the special jury prize.

From the mid-1970s onward, however, women moved decisively to the centre of his films. Their quests for lost or absent persons become searches for identity itself. Surrounded by men who are corrupt, paranoid and indecisive, women fight back and take up the sword – sometimes literally – to defend their territory. These films fuse the ceremonial legends of the past with contemporary life and move beyond the confines of the victimised female figures common in Iranian cinema.

The Stranger and the Fog (1974), a bold attack on religious conformity and an uncanny anticipation of the revolution, marked the beginning of this new period. In The Raven (1977) – an inquiry into media, image, and memory – the woman is fully central. Here, she is a deaf teacher who becomes obsessed with the image of a missing woman. Her investigation uncovers a far larger lost identity: early 20th-century Tehran.

In The Ballad of Tara (1979), which centres on the ghost of a dead warrior who falls in love with a widow in a coastal village, Beyzaie reworked the samurai epics of Akira Kurosawa through a feminist lens. The completion of the film coincided with the revolution, and it was subsequently banned indefinitely – not so much for its political symbolism as for its portrayal of a woman who is both desired and fully in command of her own destiny.

From Travellers (1992) to his final film, When We Are All Sleep (2009), Beyzaie continued to offer variations on the theme of women searching for identity, often through the act of identifying others. These later works were developed in close collaboration with his second wife, the actor Mojdeh Shamsai.

Much of this period, however, was marred by sustained harassment from the Iranian regime, including acts of punitive retaliation such as his dismissal from the theatre department of the University of Tehran, where he had taught since 1973. During periods when he was unable to work as a director, Beyzaie wrote screenplays that were filmed by others and edited other film-makers’ work. Eventually, frustrated by the situation, he left Iran in 2010 for Stanford University, where he taught in the Iranian Studies programme and staged plays he had long been prevented from performing in Iran.

In the wake of his death, Iranian director Jafar Panahi said: “We learned from him how to stand against forgetfulness.” Another film-maker, Asghar Farhadi, noted the bitter irony that “the most [culturally] Iranian of all Iranians died so far from Iran.”

There is yet another bitter irony. Two weeks before his death, what remained of Cinema Iran was burned to the ground, as if a final symbolic moment from a Beyzaie film marking the end of a major chapter in Iranian cultural history. Yet the restoration of Beyzaie’s classic films – including two undertaken under the auspices of Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project – has only deepened and expanded his reputation, both inside and outside Iran. This is a Cinema Iran that no fire can erase.